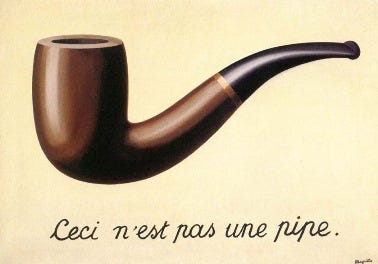

the treachery of images and the unity of Existence

“...they remain satisfied with looking at the shadows cast by the sun”

Below is reproduced the beginning of an essay recently published at Theophaneia. Anyone who wishes to read the piece in its entirely is encouraged to follow the link. There is no paywall.

In a riddle whose answer is chess, what is the only word that is prohibited?

—Jorge Luis Borges, “the Garden of the Forking Paths”1

The Japanese philosopher and professor of Islamic studies Toshihiko Izutsu delivered a riveting public lecture at the Fifth East-West Philosophers’ Conference in Hawaii in June of 19692 on a school in Eastern and Islamic metaphysics that he refers to as “the unity of existence” school.3 In the lecture, Izutsu suggests that whereas philosophy in the East has flourished into a cornucopia of different philosophical and religious schools, the West, “broadly speaking, presents a fairly conspicuous uniformity of historical development from its pre-Socratic origin down to its contemporary forms.”4 All of the other merits of Izutsu’s lecture aside, this is, by all accounts, a tendentious reading of Western thought and I hope, in some respect at least, and to the extent of my ability, to remedy it in the following essay. Moreover, I hope to show how the sublime teaching on “the unity of existence” that he presents, which is traditionally reserved for “the privileged of all privileged people,”5 is perhaps most abundantly manifest not among any of the philosophical and religious outlooks that Izutsu appeals to, or even any that he does not, but rather most definitively conveyed in the very scenes of the Gospels themselves and the words of the New Testament.

Izutsu begins the lecture by characterizing the “unity of existence” school in terms that demonstrate his mastery of the teaching and which betray not only an academic, but also an experiential, comprehension of the transformations in question.. He begins by laying the groundwork necessary to grasp the essential thesis of this view with a brief excursus into grammatical predication and the relationship that the medieval philosophers established between essence or substance, and accident or property:

We constantly use in our daily conversation propositions whose subject is a noun and whose predicate is an adjective: for example: “The flower is white,” “This table is brown” etc. On the same model we can easily transform an existential proposition like: “The table is” or “The table exists” into “The table is existent.”6 Thus transformed, “existence” is just an adjective denoting a quality of the table. And the proposition “The table is existent” stands quite on a par with the proposition “The table is brown,” for in both cases the subject is a noun denoting a substance called “table,” while the predicate is an adjective indicating grammatically a property or accident of the substance.7

With the somewhat ironic assumption of vicariousness characteristic of many Eastern masters, the speaker observes that:

The philosophers belonging to the school of thought which I am going to talk about, chose to take a position which might look at first sight very daring or very strange. They asserted that, in the sphere of external reality, the proposition: “The table is existent” as understood in the sense of substance accident relationship turns out to be meaningless. For in the realm of external reality there is, to begin with, no self-subsistent substance called “table,” nor is there a real accident called “existence” to come to inhere in the substance.8

This mode of thinking is, according to “the unity of existence” school, something like an inversion of the proper order of things; truth seen “through a glass, darkly.” Indeed, Izutsu’s description alludes to the argument embodied in Plato’s iconic Allegory of the Cave

The whole phenomenon of a table being qualified by “existence” turns into something like a shadow-picture, something which is not wholly illusory but which approaches the nature of an illusion. In this perspective, both the table and “existence” as its accident begin to look like things seen in a dream.9

Indeed he explicitly references the famous scene from Book VII of the Republic later in the talk:

Like the men sitting in the cave in the celebrated Platonic myth, they remain satisfied with looking at the shadows cast by the sun10

Let it be observed that it is not, directly, the sun which casts these shadows in Plato’s allegory, but rather “a fire is blazing at a distance.”11 Still, the point remains that a substantiality is attributed to phenomena that they cannot really bear. The argument, in both instances, then, amounts to the assertion that the objects and phenomena of ordinary perception do not exist in the way they are supposed…

Continue reading at Theophaneia

El jardín de senderos que se bifurcan (1941), which was republished in its entirety in Ficciones (Fictions) in 1944

convened under the theme of The Alienation of Modern Man

1

12

Arguably, these are not equivalent since in the first statement, the predicate is also the verb of the sentence and hence denotes a sustained activity while in the second, the verb has been retained in the copula and the predicate then is somewhat redundant. In other words, in the second case, the signification of the copula is more or less identical with the statement’s predicate. But the merit of this lecture is too much to risk derailing it with a quibble like this.

2

2

3

5

Though in an extended sense of the conceit: where do we imagine the wood to fuel the fire in question had its origin if not in captured sunlight?

I remember reading from Eliot Deutsch in 1969, same conference in Hawaii. "Advaita Vedanta and its Philosophical Reconstruction". So, we are very close on this subject. Lately, it has gravitated to Goethe's so-called, "Primal Phenomenon", which Rudolf Steiner made even more evident in his books in honor of Goethe. We need to become objective human beings, first and foremost. This means reversing subject-object, and making it object-subject. This is the main priority of the New Yoga Will, which Steiner amply describes here, and even with diagrams:

https://rsarchive.org/Lectures/MissMich/19191130p01.html

Great article Max. I couldn’t help thinking of George MacDonald’s use of shadows in his fairytale The Golden Key. I have also been following the golden thread of myth and story and iconography, so it was wonderful to see you tie them all together! I’d love to hear more from you on these.