The seven days after Palm Sunday leading to Easter are sometimes called “Holy Week,” and each day presents scene or episodes that I think over and contemplate and I would like to invite readers to do that with me.

ὁ δίκαιος μαστιγώσεται, στρεβλώσεται, δεδήσεται, ἐκκαυθήσεται τὠφθαλμώ, τελευτῶν πάντα κακὰ παθὼν ἀνασχινδυλευθήσεται καὶ γνώσεται ὅτι οὐκ εἶναι δίκαιον ἀλλὰ δοκεῖν δεῖ ἐθέλειν.

The just man will have to endure the lash, the rack, chains, the branding-iron in his eyes, and finally, after every extremity of suffering, he will be crucified, and so will learn his lesson that not to be just, but to seem just, is what we ought to desire.1

Good Friday of Holy Week dawns with the conclusion of the show-trial of Jesus and his interrogation at the hands of Pontius Pilate after being handed over to the latter by the Pharisees. It ends with his death on the Cross at sundown. I would like to explore some of these scenes in the reflection to follow but first it seems necessary to take the bull by the horns and address the question of why it is called “Good.” As I have noted on numerous occasions now, there is no limit to what could be written about these proceedings so I must remain content to offer a few remarks with the hope that they may be of value to some readers

Returning to the immediate question at hand: it’s hard to understand how a day that encompasses the scenes described can be adorned with such an qualifier—“Bad Friday” or “Black Friday” or Satan’s Friday” would each seem like more suitable epithets for such an occasion. And as Jesus himself sayeth,

why callest thou me ‘good’? there is none good, save God alone”2

But here precisely is the keyhole of insight through which we can peer to understand this connection. Doctrinally, today is called “Good Friday,” because the sacrifice of Jesus Christ made possible the salvation of souls. But an answer not understood is not an answer but a evolution of the question. What the doctrine means in reality is, of course, not settled by having established it, and the Easter mystery is an invitation for us to meditate precisely on what the doctrine means and not just what it says. For now suffice it to conclude that if “none is good, save one, that is, God,” then this Friday is called “good” because God must be present.

How and in what manner God is present is part and parcel of the mystery of Easter. Many people imagine that God demanded a sacrifice like a tribute for human sin, but this is a ham-fisted anthropomorphism if the comparison is taken literally. When people suggest that God is petty or vengeful and they assume he must be just like them, they really haven’t said anything about God. Instead, they have only succeeded to betray the narrowness of their own imaginations and the ineptness of the latter to convey anything about their apparent subject. But the purpose of Scripture is to challenge the narrowness of our conceits. Jesus’s Crucifixion was never “demanded” by God in the way that a child demands compensation for a perceived injustice. Instead, it makes manifest, on the stage of history, the very fact that Plato, having observed the fate of his teacher, had already predicted would befall the Perfect Man should he ever set foot in this world.

Modern people find it offensive, in Genesis, when God demands that Abraham sacrifice his own son Isaac on Mt. Moriah. Of course, a knee jerk reaction like this makes it impossible to understand the meaning of just about anything at all. Moreover, God sends an angel to stay his hand in any case. But this troubling scene from the Old Testament, when it is indexed to the Gospel narrative. Grasping this connection between Testaments Old and New discloses something about time itself, even as we experience it in our own lives. We never truly comprehend the meaning of the events that we live through except in the fullness of time. From the temporal view, Abraham appears to betray Isaac:

7And Isaac spake unto Abraham his father, and said, My father: and he said, Here am I, my son. And he said, Behold the fire and the wood: but where is the lamb for a burnt offering? 8And Abraham said, My son, God will provide himself a lamb for a burnt offering: so they went both of them together.

But in light of the Gospel, the message of this scene is abundantly clear. God did indeed provide the Lamb, and Abraham and Isaac prefigured the very events that the Father and the Son would later bring to fruition. Aristotle defined tragedy as as

…an imitation of an action that is serious, complete, and of a certain magnitude…in the form of action, not of narrative; through pity and fear effecting the proper catharsis (κάθαρσις) of these and similar emotions”3

“Tragedy,” from τραγῳδία, is contracted from trag(o)-aoidiā, which is, being interpreted, “goat song” (tragos, “he-goat”4 & aeidein, “to sing” (cf. “ode”)). Scholars speculate that a goat was offered as a prize in a competition of choral dancing or that the dancing was performed prior to the creature’s ritualized sacrifice. But that tragōidia stems from the Greek word for “goat” is an etymology that is infinitely suggestive when read in concert with the Jewish scriptures, and particularly, the well-known passage in Leviticus that describes the “sacrificial goat” and the “scapegoat” and which has been seen by many to prefigure the deed of Christ:

7And he shall take the two goats, and present them before the LORD at the door of the tabernacle of the congregation. 8And Aaron shall cast lots upon the two goats; one lot for the LORD, and the other lot for the scapegoat. 9And Aaron shall bring the goat upon which the LORD’S lot fell, and offer him for a sin offering. 10But the goat, on which the lot fell to be the scapegoat, shall be presented alive before the LORD, to make an atonement with him, and to let him go for a scapegoat into the wilderness….21And Aaron shall lay both his hands upon the head of the live goat, and confess over him all the iniquities of the children of Israel, and all their transgressions in all their sins, putting them upon the head of the goat, and shall send him away by the hand of a fit man into the wilderness: 22And the goat shall bear upon him all their iniquities unto a land not inhabited: and he shall let go the goat in the wilderness.

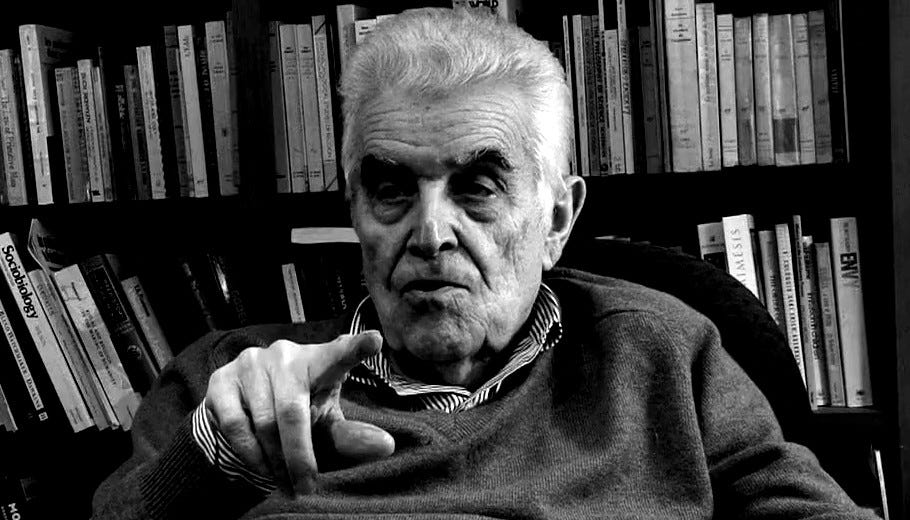

These two goats have become conflated with time, but the twofoldness prefigures the release of Barabbas on one hand, and the so-called “dual nature of Christ” on the other. In short, if we ask, with Tertullian, “What hath Athens to do with Jerusalem?” we can only do that by averting our eyes and looking away from that ostentatious point on Calvary where they intersect. Again, the significance of these puzzles can be discerned in light of the Gospels, or can be experienced as musical history, in the manner that a V7 chord resolves into the tonic in the Easter mystery. A great deal more could be said about tragedy in relation to René Girard’s theory of the scapegoat mechanism but rather than expand on this theme here, I will instead kindly point readers to the linked essay below.

One final point about “tragedy” before proceeding with a brief survey and commentary on crucial scenes from Good Friday: can it really be considered an accident that the language of the New Testament was the same language out of which the dramatic arts were born? To understand Scripture as though it were talking about “other people” is not to understand Scripture.

Now to the scenes of Good Friday. In the Evangelist’s account:

28Then led they Jesus from Caiaphas unto the hall of judgment: and it was early; and they themselves went not into the judgment hall, lest they should be defiled; but that they might eat the passover. 29Pilate then went out unto them, and said, What accusation bring ye against this man? 30They answered and said unto him, If he were not a malefactor, we would not have delivered him up unto thee. 31Then said Pilate unto them, Take ye him, and judge him according to your law. The Jews therefore said unto him, It is not lawful for us to put any man to death: 32That the saying of Jesus might be fulfilled, which he spake, signifying what death he should die.

The Pharisee-logic here is quite funny as a paradigmatic example of the fallacy of petitio principii. When Pilate asks, “What accusation bring ye against this man?” he is already attempting to determine the evidentiary basis on which this man accused of being a malefactor. To respond, as the Pharisees did that “he is a malefactor because we have accused him of being one and delivered him up to thee on these grounds” is, well, begging the question. And again, “you ought to put him to death because it is not lawful for us to do so,” whereas the real question at stake is on what grounds he should be put to death to begin with. Those grounds, are, of course, Calvary-Golgotha. Legend has it that Adam’s corpse is buried on Golgotha, which is, being interpreted, “the place of the skull.” Christ as “the New Adam” follows the Old Adam down to Hades but does not abide there.

Continuing with the Evangelist’s account:

33Then Pilate entered into the judgment hall again, and called Jesus, and said unto him, Art thou the King of the Jews? 34Jesus answered him, Sayest thou this thing of thyself, or did others tell it thee of me? 35Pilate answered, Am I a Jew? Thine own nation and the chief priests have delivered thee unto me: what hast thou done?

Pontius Pilate is clearly troubled by Jesus but, as it is said, for evil to triumph, it is enough for good men to do nothing. Matthew offers a corroborating account:

11And Jesus stood before the governor: and the governor asked him, saying, Art thou the King of the Jews? And Jesus said unto him, Thou sayest. 12And when he was accused of the chief priests and elders, he answered nothing. 13Then said Pilate unto him, Hearest thou not how many things they witness against thee? 14And he answered him to never a word; insomuch that the governor marvelled greatly.

Jesus doesn’t demand belief but leaves people free. This is one of the most insidious elements to forensic investigations into “the historical Jesus.” If someone recounts a story to me, it is unrealistic to demand that he furnish empirical proof for each scene before I will hear it. In many cases, the only way I could prove what I myself was doing twenty minutes in the past is to appeal to witnesses, and if their testimony is preemptively rejected, then so too must be any hope of establishing an evidentiary basis for it. If this is impossible after only twenty minutes have elapsed, how much more after twenty centuries. Moreover, if, hypothetically, dispositive historical proof could be furnished, it would change my relationship of belief in Christ to one of belief in science. It may seem that this is of little moment but notice it entails an entirely different state of soul as well as an entirely different disposition of loyalty.

John picks up the narrative:

36Jesus answered, My kingdom is not of this world: if my kingdom were of this world, then would my servants fight, that I should not be delivered to the Jews: but now is my kingdom not from hence.

This hearkens to the Third Temptation of Christ in the desert, as recounted in the beginning of Matthew:

8Again, the devil taketh him up into an exceeding high mountain, and sheweth him all the kingdoms of the world, and the glory of them; 9And saith unto him, All these things will I give thee, if thou wilt fall down and worship me. 10Then saith Jesus unto him, Get thee hence, Satan: for it is written, Thou shalt worship the Lord thy God, and him only shalt thou serve. 11Then the devil leaveth him, and, behold, angels came and ministered unto him.

Dostoevsky provides a masterful commentary on this temptation in the iconic “Grand Inquisitor” scene from the Brothers Karamazov. The Grand Inquisitor argues that, whatever Jesus believes, people actually wanted him to be Prince of this World, and if he insisted on refusing the office, then the task would fall to someone else to assume the responsibility that Jesus had eschewed. To demand rather that people “take up your cross and follow me,” and tread the Via dolorosa after him was a chimeric and unreasonable expectation:

But I ask again, are there many like Thee? And couldst Thou believe for one moment that men, too, could face such a temptation? Is the nature of men such, that they can reject miracle, and at the great moments of their life, the moments of their deepest, most agonizing spiritual difficulties, cling only to the free verdict of the heart?5

Pilate seems to vindicate the Grand Inquisitors line of reasoning when the former fails to comprehend how someone could be a king and yet renounce worldly power:

37…Art thou a king then?

Pilate asks. Again, Jesus’ answer appears to unsettle him:

Thou sayest that I am a king.

Jesus’ answer might seem like Pharisee-logic but it is something else entirely. To wit, Jesus is again requiring that people establish their relationship with his spirit in freedom and not through passivity or compulsion. What may at first appear as a contradiction between his resolute silence in Matthew’s account and his laconic howbeit more elaborate responses in John can then be reconciled with little difficulty when the significance of the scene is apprehended. Jesus elaborates in his answer to Pilate:

To this end was I born, and for this cause came I into the world, that I should bear witness unto the truth. Every one that is of the truth heareth my voice. 38Pilate saith unto him, What is truth? And when he had said this, he went out again unto the Jews, and saith unto them, I find in him no fault at all. 39But ye have a custom, that I should release unto you one at the passover: will ye therefore that I release unto you the King of the Jews? 40Then cried they all again, saying, Not this man, but Barabbas. Now Barabbas was a robber.

This scene brings us back to the subject of “the scapegoat,” introduced at the outset of this contemplation, and that can, indeed, be fittingly regarded as the keynote of this day.

Friday

planet: Venus

quality: love, passion (i.e. as opposed to action)

color: green

vowel: ah

organ: kidneys (34 “But one of the soldiers with a spear pierced his side, and forthwith came there out blood and water.”)

metal: copper

tree: birch

Plato’s Republic 2.361e–362a. In the Gospel of Matthew, Pilate’s wife uses the word dikaios, when she tells him her dream: “Have thou nothing to do with that just man (dikaios): for I have suffered many things this day in a dream because of him.” (Mt 27:19) Pilate should have listened to his wife, just as Caesar should have listened to his.

cf. Mark 10:17-22:

17And when he was gone forth into the way, there came one running, and kneeled to him, and asked him, Good Master, what shall I do that I may inherit eternal life? 18And Jesus said unto him, Why callest thou me good? there is none good but one, that is, God. 19Thou knowest the commandments, Do not commit adultery, Do not kill, Do not steal, Do not bear false witness, Defraud not, Honour thy father and mother. 20And he answered and said unto him, Master, all these have I observed from my youth. 21Then Jesus beholding him loved him, and said unto him, One thing thou lackest: go thy way, sell whatsoever thou hast, and give to the poor, and thou shalt have treasure in heaven: and come, take up the cross, and follow me. 22And he was sad at that saying, and went away grieved: for he had great possessions.

Aristotle, Poetics, 1449b

this gives a new significance to the astronomical fact that Jesus was a Capricorn, which is, “horned-goat.”

Brothers K, V.5

It seems quite clear that the demand for the crucifixion of Christ, and the release of Barabbas is in full support of High Priest Caiaphas, who is looking for a scapegoat with this testimony:

47 Therefore the chief priests and the Pharisees convened a council, and were saying, “What are we doing? For this man is performing many signs. 48 If we let Him go on like this, all men will believe in Him, and the Romans will come and take away both our place and our nation.” 49 But one of them, Caiaphas, who was high priest that year, said to them, “You know nothing at all, 50 nor do you take into account that it is expedient for you that one man die for the people, and that the whole nation not perish.” 51 Now he did not say this on his own initiative, but being high priest that year, he prophesied that Jesus was going to die for the nation, 52 and not for the nation only, but in order that He might also gather together into one the children of God who are scattered abroad. 53 So from that day on they planned together to kill Him. John 11

The Roman governor, Pilate, on the other hand, in wanting to be fair, sees "no guilt in Him". He eventually gets caught between a rock and hard spot when the chief priests say, "We have no king but Caesar". John 19:15

37 Therefore Pilate said to Him, “So You are a king?” Jesus answered, “You say correctly that I am a king. For this I have been born, and for this I have come into the world, to testify to the truth. Everyone who is of the truth hears My voice.” 38 Pilate said to Him, “What is truth?”

And when he had said this, he went out again to the Jews and said to them, “I find no guilt in Him. 39 But you have a custom that I release someone ]for you at the Passover; do you wish then that I release for you the King of the Jews?” 40 So they cried out again, saying, “Not this Man, but Barabbas.” Now Barabbas was a robber. John 18

Pilate should have listened to his wife, just like Caesar should have listened to his. It represents that we should attend not only to our rational sides but also our intuitive ones.

Pilate again, impotently, tries to avoid responsibility by allowing them to free one of the prisoners:

20But the chief priests and elders persuaded the multitude that they should ask Barabbas, and destroy Jesus.

This illustrates the ineluctable architecture of democratic consensus, which is always conditioned by non-democratic agents.

22Pilate saith unto them, What shall I do then with Jesus which is called Christ? They all say unto him, Let him be crucified. 23And the governor said, Why, what evil hath he done? But they cried out the more, saying, Let him be crucified. 24When Pilate saw that he could prevail nothing, but that rather a tumult was made, he took water, and washed his hands before the multitude, saying, I am innocent of the blood of this just person: see ye to it. 25Then answered all the people, and said, His blood be on us, and on our children. 26Then released he Barabbas unto them: and when he had scourged Jesus, he delivered him to be crucified.

The surest way never to escape Plato’s Cave is to imagine we are not imprisoned there and the surest way to guarantee we ourselves would have been among the hoi polloi crying for Christ’s death is to imagine that we would have known better.

16Then delivered he him therefore unto them to be crucified. And they took Jesus, and led him away.

17And he bearing his cross went forth into a place called the place of a skull, which is called in the Hebrew Golgotha: 18Where they crucified him, and two other with him, on either side one, and Jesus in the midst. 19And Pilate wrote a title, and put it on the cross. And the writing was, JESUS OF NAZARETH THE KING OF THE JEWS. 20This title then read many of the Jews: for the place where Jesus was crucified was nigh to the city: and it was written in Hebrew, and Greek, and Latin. 21Then said the chief priests of the Jews to Pilate, Write not, The King of the Jews; but that he said, I am King of the Jews. 22Pilate answered, What I have written I have written.

The title above the Cross seems like an accident, but everything seems like an accident until we understand the causes of things and the intentions of beings. Providence—the Will of the Father—works through creatures even while they remain unaware just like the breath moves through our lungs, animating them. Before we lived out these divine intentions in an instinctive way. In the middle, we begin to lose our way. Christ represents the dawn of our ability to participate them in full consciousness—“the power to become the sons of God, even to them that believe on his name.”