on “the Parable of the Blind Men and the Elephant” and the mystery of intentionality

on intentionality, perception, theory of knowledge

Intentionality is a technical term employed to designate the intentional, or natural directedness, of consciousness. This directedness entails an inherent “aboutness” in respect to thought. To think, we have to think about some content, and if we wish to learn about the thinking itself, we still have to think about some content, only now the content it nothing other than thinking itself. The paradox is akin to seeing a mirror or seeing a reflection. We look in the mirror to see the reflection, and look at the reflection to see the mirror. As Rudolf Steiner observes:

The reason why we do not observe the thinking that goes on in our ordinary life is none other than this, that it is due to our own activity. Whatever I do not myself produce, appears in my field of observation as an object; I find myself confronted by it as something that has come about independently of me. It comes to meet me. I must accept it as something that precedes my thinking process, as a premise. While I am reflecting upon the object, I am occupied with it, my attention is focused upon it. To be thus occupied is precisely to contemplate by thinking. I attend, not to my activity, but to the object of this activity. In other words, while I am thinking I pay no heed to my thinking, which is of my own making, but only to the object of my thinking, which is not of my making.

I am, moreover, in the same position when I enter into the exceptional state and reflect on my own thinking. I can never observe my present thinking; I can only subsequently take my experiences of my thinking process as the object of fresh thinking. If I wanted to watch my present thinking, I should have to split myself into two persons, one to think, the other to observe this thinking. But this I cannot do. I can only accomplish it in two separate acts. The thinking to be observed is never that in which I am actually engaged, but another one. Whether, for this purpose, I make observations of my own former thinking, or follow the thinking process of another person, or finally, as in the example of the motions of the billiard balls, assume an imaginary thinking process, is immaterial.

…

Were we to refrain from thinking until we had first gained knowledge of it, we would never come to it at all. We must resolutely plunge right into the activity of thinking, so that afterwards, by observing what we have done, we may gain knowledge of it. For the observation of thinking, we ourselves first create an object; the presence of all other objects is taken care of without any activity on our part.

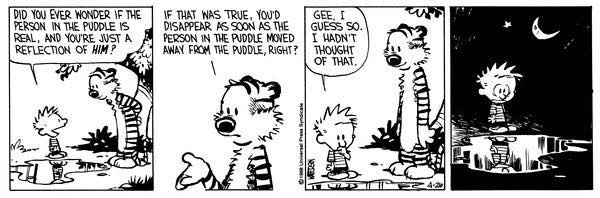

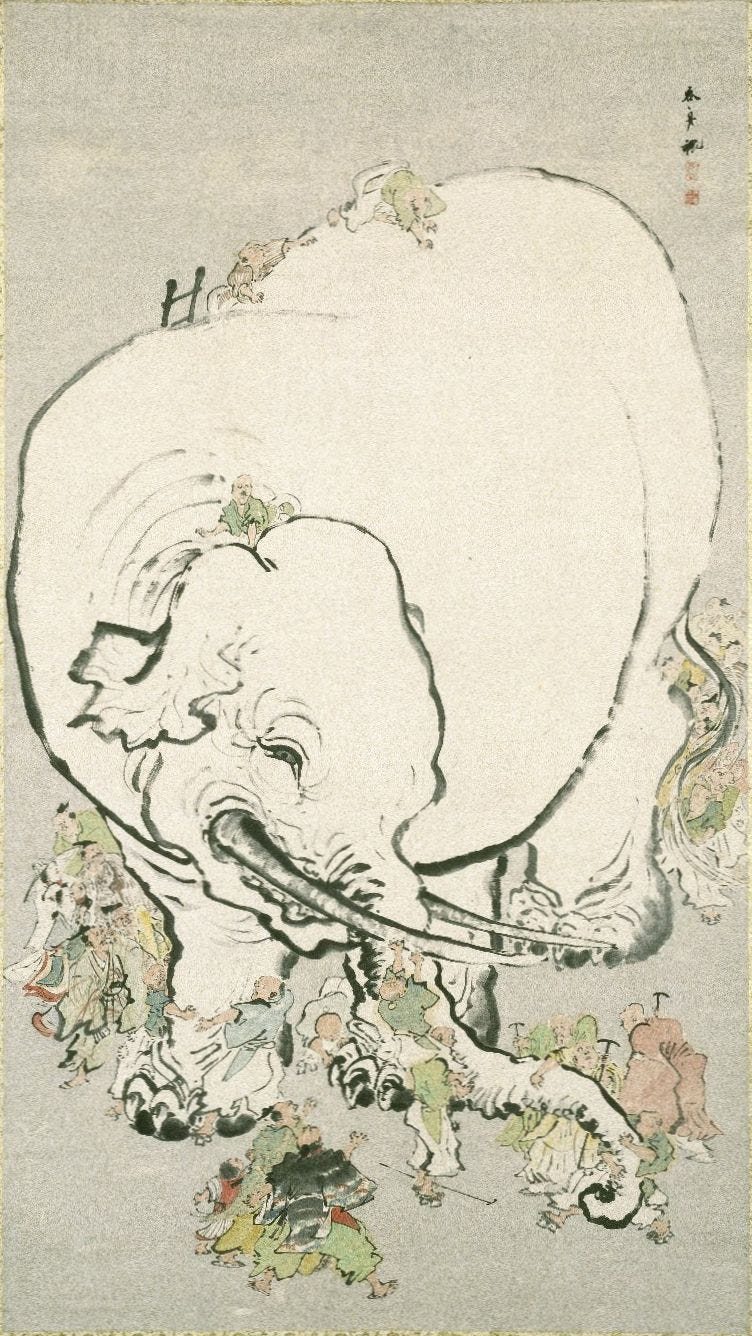

Now consider the well-known parable of “The Blind Men and the Elephant.” Each blindman encounters the as-of-yet-unknown thing in a particular aspect and at once interprets it in light of a familiar item: “the elephant is like a rope,” “a snake,” “a tree,” and so on. The blindmen, as of yet lacking the idea of “elephant,” were, by this token, unable to intend “elephant” and, ipso facto, unable to perceive the eventual elephant that they encountered. Because they were able to intend the familiar items above, however, they instead interpreted their experience in light of these ideas, ready-to-hand as they were.

To really grasp what is at stake here, it’s important to separate intentionality from our colloquial uses of the term but, once done, then its essential to recombine these purified elements together again, alchemically, as it were. In the same spirit, I undertook a similar exercise vis-à-vis the term theory in the inaugural post of this Substack and these two exploration dovetail neatly the one into the other.

People often employ “intentionality” as a synonym for “intention.” “Intention,” is of course, the substantive form of “intend,” which we employ, in turn, as a synonym for “mean.” So, consider: the men were unable to mean “elephant”—or to allow their sense-impressions to mean that—and as a result, unable to perceive one. In other words, for our sense-encounters to mean anything altogether, we have to be able, concurrently, to mean, viz. to intend, that thing. A comprehension of the term intentionality gives us, as it were, the idea of “perception” and “cognition” and allows us to recognize the tissue of relation that joins the incarnate words around us to their meanings. In other words, it allows our own cognitive activity, ordinarily the transcendental condition for the perception of phenomena ulterior to it, to become itself phenomenal to us.

The blind men in the parable illustrate how we can go wrong in this. Nevertheless, by the same token, they show us what corrections need to be made to go right. It’s possible to articulate at least three fallacies of perception embodied in the blind men of the parable, which even through their falsehood can point the path to truth: as Goethe’s Mephistopheles declared, “I am a part of that power which wills continual evil and which works continual good.”1 By knowing its distortion we may perhaps better know the truth.

The first fallacy is that of extrapolation, in which the quality of one discrete perceptual encounter is extrapolated to represent the entirety of the phenomenon in question. The same spirit is behind all snap-judgments and hasty-generalizations and, by extension, most of the opinions people cherish most dearly. If we knew the moral tempters that seek to draw us, as it were, down this path, we would find pridefulness, which blinds us, and impatience, which allows us to be led. Each blind man encounters the elephant in one of its aspects, and proceeds, by inductive zeal, make the whole in the image of one of its parts.

A second fallacy is failure to perceive causality. Phenomena, which are in fact effects, are imbued with a causal primacy they do not possess.

Iconically and immemorably, imprisonment by this false conceit is depicted in Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave.” Everybody identifies himself with “the philosopher,” who questions appearances, undertakes a “steep and rugged ascent,” suffers to apprehend phenomena for which his paradigms of understanding are like so much straw,2 returns to the cave to be scorned and reviled and threatened with crucifixion if they should manage to lay hands on him, and so on. But, obviously, as long as we imagine ourselves to be the liberators, we won’t bother first to “cast out the beam out of thine own eye” and liberate ourselves from these chains of our own pretenses to knowledge. But most of us aren’t wise enough to love wisdom3 that much. As Schiller said, the anniversary of whose death in 1805 is today, “they must already be wise, to love wisdom.”4 The spirit of this fallacy is behind all superstitious animism and cargo-cults. Because of complacency, however, and lack of interest,5 we never consider that many of our behaviors and the belief-structures that underpin them are hardly more evolved. Psychological experience, for instance, and all the emotions and imaginations that it encompasses, are the effect of causal powers that ordinarily garner no more attention than the puppet-masters in Plato’s story whom nobody notices. The blind men, again, encounter the elephant in one of its discrete perceptible aspects but fail to grasp that that aspect is not its own cause, but rather the expression of a higher unity.

A third fallacy is a failure of conceit; a substitution of standpoint for understanding. The scope of our vision is substantially, if not entirely, conditioned by our expectations surrounding what our vision will disclose. We never see more than we are willing to intend, in the phenomenological meaning of this word, as explained above. As an illustration, consider how we often talk about “God.” As Meister Eckart says, “people want to look upon God with their eyes, as they look upon a cow, and want to love God as they love a cow.”6 Inclinations to idolatry and narcissism lead each person to substitute his own symbol of (the) Go(o)d—a symbol which is ultimately some reflection of himself—for “the Good-beyond-Being” that the former is meant to symbolize7 and reflect. But the symbol should be an idea and not a thing, which is to say, some particular instantiation of that idea. The symbol should be like a window and not like a cow—not alone something we see, but something also through which we look. Everyone tries to remake the truth in his own image: “For the Jews require a sign, and the Greeks seek after wisdom.”8 Of course, when God finally sent his own symbol of himself to replace the idols, we mocked him and nailed him to a tree.

What does the elephant represent? Any as of yet unknown phenomenon. The blind men are us, collectively and individually. The first of these is obvious, the second perhaps less so. But consider that we only perceive material phenomena through our senses, any single one of which is blind. What about our eyes? We see through them, not with them. Consider the healing of the blind man in the Gospel According to Mark:

22And he cometh to Bethsaida; and they bring a blind man unto him, and besought him to touch him. 23And he took the blind man by the hand, and led him out of the town; and when he had spit on his eyes, and put his hands upon him, he asked him if he saw ought. 24And he looked up, and said, I see men as trees, walking.

He still must learn to see through his eyes, which is to say, to interpret the visible signatures of phenomena, even after Christ restores his sight. We have to be able to intend something—to mean something—in order to see it. What we cannot mean, we cannot see, and when we see, it is meaning that we are seeing. Literature is rife with the motif of the blind man who outsees the rest. Consider how only Tiresias sees the truth of Oedipus’ plight, and how Gloucester had to first have his eyes plucked out as “vile jelly” before he could see his two sons in their own respective merit.

What does the parable as a whole represent? How is it possible that visible things can represent invisible ones?

Ich bin ein Teil jener Kraft, die stets das Böse will und stets das Gute schafft.

also, more elaborate and perhaps more interesting:

Ich bin ein Teil des Teils, der anfangs alles war,

Ein Teil der Finsternis, die sich das Licht gebar,

Das stolze Licht, das nun der Mutter Rang

Um Raum und Ordnung seinem Zug entlang;

Und mit den Elementen sich befeindet,

Sich Nest und Schale und Gehäus’ erfindet.

which is, being interpreted:

I am a part apart, that from the beginning was

a part of that darkness that gave birth to light,

proud light, which now with its mother strives

through space and sequence all along

in enmity against the elements

yet with and through them do I thrive

The quote comes from Mephistopheles’ conversation with Faust in the “Prologue in Heaven” in Goethe’s Faust, Part One.

In response to his friend and secretary, Reginald of Piperno, who had urged Aquinas to continue writing after he had stopped dictating the Summa Theologiae following a mystical experience during Mass on December 6, 1273, during which the Saint had an encounter with God that left him in a state of ecstasy, the Doctor Angelicus replied: “Reginald, I cannot, because all that I have written seems like straw to me (mihi videtur ut palea).

Friedrich Schiller:

Sie müßten schon weise sein, um die Weisheit zu lieben: eine Wahrheit, die Derjenige schon fühlte, der der Philosophie ihren Namen gab.

that is, uninterest and not disinterest

from sermon №52:

Many people want to look upon God with their eyes, as they look upon a cow, and want to love God as they love a cow—for the milk and cheese and profit it brings them. Thus they love God for the sake of external riches and of internal solace; but these people do not love God aright.

which is, in Middle High German:

Etliche Leute wollen Gott mit ihren Augen sehen, wie sie eine Kuh sehen, und ihn lieben, wie sie eine Kuh lieben - um der Milch und des Käses und des Nutzens willen, den sie davon haben. So ist es mit den Leuten, die Gott um äußeren Reichtums oder inneren Trostes willen lieben. Sie lieben Gott nicht recht, wenn sie ihn um ihres eigenen Vorteils willen lieben.

symbolize, that is “cast together,” “gather together,” “ponder”

1 Corinthians 1:22

22For the Jews require a sign, and the Greeks seek after wisdom: 23But we preach Christ crucified, unto the Jews a stumblingblock, and unto the Greeks foolishness; 24But unto them which are called, both Jews and Greeks, Christ the power of God, and the wisdom of God.

cf. footnote №2

One of my favourite parables

Hi Max,

I think your initial reference to Steiner's "billiard ball" analogy from PoF is a good one. Yet, he would supplant it a number of years later by what he says in his book, Outline of Occult Science, from 1910. In the first chapter, the character of occult science is described. We have already had this discussion. This is what gives modern academics, in their progressive higher education, the dilemma they have, and largely with the liberal arts curriculum. We need to extend the present limits into the domain of occult science. And, we know that CIIS is resistant to doing that. My own prospectus appeals have fallen on deaf ears for many years. That is why I am reduced to writing on Substack. At least they care in the AI frame of reference. ;)

Yet, it is always good writing to you. I see it as a kind of renewal of the so-called, "Great War", between C.S. Lewis, and Owen Barfield. My understanding is that it was a relatively short war, and largely dealing with metaphysics. Lewis was the one that tired out in the exchanges, but would grow an imaginative cognition based on Barfield's inspirations.