on the Four Causes and The Advancement of Learning

“I am able to bend my limbs, and this is why I am sitting here in a curved posture”

confer:

Francis Bacon (The Advancement of Learning, 1605):

Natural science...doth make inquiry, and take consideration of the same natures : but how? Only as to the Material and Efficient causes of them, and not as to the Forms1...

and again (Instauratio magna, 1620)

Matter rather than Forms should be the object of our attention, its configuration and changes of configuration, and simple action, and laws of action or motion, for forms are figments of the human mind, unless you call those laws of action Forms.2

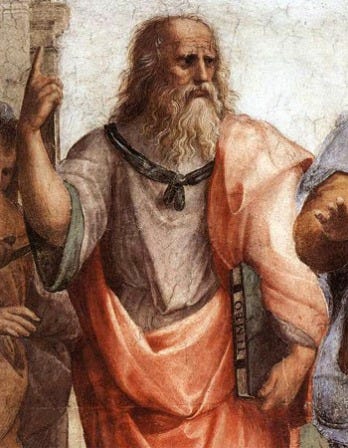

Plato (Phaedo, 365 BC):

As I proceeded, I found my philosopher altogether forsaking mind or any other principle of order, but having recourse to air, and ether, and water, and other eccentricities. I might compare him to a person who began by maintaining generally that mind is the cause of the actions of Socrates, but who, when he endeavoured to explain the causes of my several actions in detail, went on to show that I sit here because my body is made up of bones and muscles; and the bones, as he would say, are hard and have joints which divide them, and the muscles are elastic, and they cover the bones, which have also a covering or environment of flesh and skin which contains them; and as the bones are lifted at their joints by the contraction or relaxation of the muscles, I am able to bend my limbs, and this is why I am sitting here in a curved posture—that is what he would say, and he would have a similar explanation of my talking to you, which he would attribute to sound, and air, and hearing, and he would assign ten thousand other causes of the same sort, forgetting to mention the true cause, which is, that the Athenians have thought fit to condemn me, and accordingly I have thought it better and more right to remain here and undergo my sentence; for I am inclined to think that these muscles and bones of mine would have gone off long ago to Megara or Boeotia—by the dog they would, if they had been moved only by their own idea of what was best, and if I had not chosen the better and nobler part, instead of playing truant and running away, of enduring any punishment which the state inflicts. There is surely a strange confusion of causes and conditions in all this. It may be said, indeed, that without bones and muscles and the other parts of the body I cannot execute my purposes. But to say that I do as I do because of them, and that this is the way in which mind acts, and not from the choice of the best, is a very careless and idle mode of speaking. I wonder that they cannot distinguish the cause from the condition, which the many, feeling about in the dark, are always mistaking and misnaming.3

Bacon’s rejection of Formal Cause (causa formalis, εἶδος) from the scope of scientific inquiry represents an iconic moment in intellectual history. Bacon is somewhat equivocal as to whether he is arguing that a consideration of Forms doesn’t belong within the scientific methodology or whether he thinks they don’t exist altogether but this difference is largely explained by a trend towards intensification of his contest against the classical paradigm throughout the course of his career.4 Regardless of his personal view, the fact that Science excluded Forms from its purview coupled with the ascendancy of its influence over this civilization led to the gradual identification of scientific descriptions with truth itself so, in respect to the history of ideas, the difference is moot.

Naïve people imagine that Science consists in discovering things about Nature but this ignores the more fundamental project that is transpiring concurrently with the apparent discoveries being made. To wit, the more fundamental project is the reconceptualization of Nature by Science in its own image. It is in light of such reconceptualization that these discoveries are, as a rule, possible. David Bentley Hart explains this better than I ever could:

The older fourfold nexus of causality [Aristotelian causality] was not, that is to say, a defective attempt at modern physical science, but was instead chiefly a grammar of predication, describing the inherent logical structure of anything that exists insofar as it exists, and reflecting a world in which things and events are at once discretely identifiable and yet part of the larger dynamic continuum of the whole. It was a simple logical picture of a reality in which both stability and change can be recognized and designated.

...

The extraordinary fruitfulness of modern scientific method was achieved, before all else, by a severe narrowing of investigative focus; and this involved the willful shedding of an older language of causality that possessed great richness, but that also seemed to resist empirical investigation. The first principle of the new organon was a negative one: the exclusion from scientific investigations of any consideration of possible formal and final causes, and even of a distinct principle of “life,” in favor of an ideally inductive method, supposedly purged of metaphysical prejudices, according to which all natural systems were to be conceived as mere machine processes, and all real causality as exchanges of energy between material masses. Everything physical became, in a sense, reducible to the mechanics of local motion; even complex organic order came to be understood as the purely emergent result of physical forces moving through time from past to future as if through Newtonian space.

Everything came to be regarded as ultimately reducible to the most basic level of material existence, and to the mathematically calculable physical consequences of purely physical antecedent causes. And while at first many of the thinkers of early modernity were content to draw brackets around material nature, and to allow for the existence of realities beyond the physical—mind, soul, disembodied spirits, God—they necessarily imagined these latter as being essentially extrinsic to the purely mechanical order that they animated, inhabited, or created. Thus, in place of classical theism’s metaphysics of participation in a God of infinite being and rationality, these thinkers granted room only for the adventitious and finite Cosmic Mechanic or Supreme Being of Deism or (as it is called today) Intelligent Design Theory. And, in place of the spiritual soul of antique thought, they allowed for only Cartesian dualism’s “ghost in the machine.”5

In the epigraphs above, Bacon’s suggestion that Material Cause alone can provide for a sufficient understanding or explanation of a phenomenon or scenario is juxtaposed with Plato’s illustration of the ineluctable absurdity of such a view, or, more specifically, that adopting such a view entails discarding the principle of sufficient reason and ultimately dispensing with the possibility of understanding altogether in favor of a crude pseudo-empirical description,6 and no number of statistical regularities, no matter how accurate, can replace what has been lost. The causa formalis is the the idea, pattern, paradigm, or intelligible essence (είδος) that allows any intellect to recognize a phenomenon as just that phenomenon which it is, and not some other phenomenon that it is not. Thus, formal causality is the ground of logic: the laws of non-contradiction, self-identity, and excluded middle are implicit in a thing’s intelligibility and are derived from, and pertinent to, the Form of a thing and not its Matter alone. In light of this situation, can it be any surprise that the greatest scientific minds now proclaim that Nature is both deterministic and random, that it is both 13.8 billion years old and that absolute time doesn’t exist, that the great equations of physics are both mathematical abbreviations of Nature’s powers and also explanations of it? After all, the classical “grammar of predication” that, in Hart's words, “was capable of describing the inherent logical structure of anything that exists insofar as it exists” has been cast out in favor of a hamfisted quasi-materialism whose own premises are hardly coherent among themselves, let alone capable of providing for a complete understanding of Nature.

On a final note: the substitution of Formal and Final Causality with statistical laws is comparable to the replacement of philology with linguistics. In his farewell address, J.R.R. Tolkien lamented precisely this trend, progressing apace in his day and, in our own, thoroughly accomplished. The difference can perhaps best be conveyed by the observation that a study in the field of linguistics can be performed on a language that the researcher does not even know, whereas it would be senseless to think of sustaining a philological relationship in that way. Most studies in the field of linguistics must be performed by computers because they concern quantitative and statistical measurements of language usage and patterns a grasp of which exceeds the capacity of human intelligence whereas a philological inquiry must be sustained by a mind and soul and intelligence capable of experiencing language on its own terms instead of transposing it into data.

appendix of the fourfold nexus of Aristotelian causality:

In the epigraph, Bacon draws on the Aristotelian distinction between morphē (μορφή, literally “shape” or “form”) and hyle (ύλη, literally “wood” or “matter”). Scholastic thinkers had elaborated this distinction under the Latin terms forma and materia, which Bacon referred to in their anglicised forms in the quote above. Where Aristotle and the Scholastics distinguished these two aspects of a single substance, Bacon divides them and posits substance to be a purely material thing. Thus he continues his project, which by 1620 he conceived of as not merely an “Advancement of Learning” as in 1605, but as an Instauratio magna—a “Grand Restoration of the Sciences.” After rejecting the notion of forms in the Aristotelian sense, Bacon replaces them with laws:

It may be that nothing really exists except individual bodies, which produce real motion according to law; in science it is just that law, and the enquiry, discovery, and explanation of it, which are the fundamental requisite both for the knowledge and for the control of Nature. And it is that law, and its “clauses,” which I mean when I use (chiefly because of its current prevalence and familiarity) the word “forms.”7

The substitution of laws for forms in the conception of Nature is a change of immense significance. It is analogous to the difference between a regulation, and the concrete behaviour that the former may intend to regulate. To disclose the import of Bacon’s decree, a contrast with its counterpart will prove exceedingly illuminating.8 A brief excursion into Aristotelian physics, therefore, is in order. Specifically, I will explicate Aristotle’s notion of causality in order to show how matter was conceived in pre-modern times—before Bacon decisively cleft it asunder from its forms with the incision of his postulates.

In the fourth century BC, Aristotle had delineated four causes—material, efficient, formal, and final—which he believed together could encompass the necessary conditions for a given being.9 Plainly, “cause” in this sense transcends the common usage of that term, which today refers only to the efficient one—and sometimes the material—in Aristotle’s more comprehensive scope of those terms. In this respect, Aristotle’s causes might be thought of as the four “becauses.” To illustrate Aristotle’s notion of causality, one may imagine the very chandelier that, in the autumn of 1602, sparked Galileo’s insight into the laws of isochronous motion of a pendulum. The object’s material cause (causa materialis, or ΰλη) just is the matter “out of which” the thing is made. For simplicity’s sake we can say it is bronze and glass. The efficient cause (causa movens, or κινήσεως) appears as the force “by which” a thing comes to be. Alternatively, it could be understood as the necessary change in order to impress the realisation of the formal cause into the material one. One can include the craftsman’s technique, or skilled application of force, as well as the furnace or kiln that was enlisted to liquefy the materials in preparation for their moulding in this principle. With the material and efficient causes, I have concluded a survey of that which Bacon set forth as the scope of scientific inquiry.

In delimiting the domain of natural science in this manner, Bacon openly excluded formal and final causality from its scope. A brief consideration of these causes will reveal the relevance of their exclusion to the phylogeny of the hard problem of consciousness, as well as many other domains of knowledge today.10 Taking up again the example of Galileo’s swinging body, which happened to be a chandelier, the formal cause (causa formalis, idea, or είδος) is the quiddity of chandelierness which makes it an actual chandelier instead of a potential one (i.e., mere glass and bronze), or something else brazen and vitreous altogether. Aristotle describes the formal cause in Metaphysics when he explains that “by form (είδος) I mean the what-it-is-to-be each thing, its prime reality.”11 One way to understand the perspective of modern thinkers in the tradition of Bacon and Galileo is to recognise the manner in which they invert, and even controvert, the view of Plato and Aristotle. Whereas the latter conceive of matter as a container (or vessel, or vehicle, or medium, etc.) for form as the content or reality, since the time of the Scientific Revolution, it is more common to see this situation reversed. Thus, the contemporary standard is to conceive of matter, not form, as the content or “being of each thing, its primary reality,” and form as something less real, like an epiphenomenon or abstraction of material configuration—a “figment of the human mind,” in Bacon’s exquisite formulation. That the latter is a common conception of mind in relation to brain activity is also a very pertinent and revealing comparison. For this reason, it is generally assumed that Nature will be understood through an analysis or anatomization of matter. In respect to the subject of this investigation, this manner of thinking leads as a matter of course to the expectation that the mind will be understood by an analysis of the brain, and neuronal activity.

To recapitulate the traditional notion of causality: the material cause is that “out of which” a thing comes to be, the efficient cause is that “by which” it comes to be, and the formal cause is “that” which comes to be. In this application, the formal cause is the design, or the intelligence that informs the application of the material and efficient causes. It is also the idea, pattern, paradigm, or intelligible form (είδος) that allows any intellect to recognize the thing as just that thing which it is, and not some other thing that it is not. Thus, formal cause is also the ground of logic, since the laws of non-contradiction, self-identity, and excluded middle are implicit in a thing’s intelligibility and are derived from, and pertinent to, the form of a thing and not its matter alone. The formal cause, being what it is, possesses the power both to actualize its being in matter and in mind (i.e., the intellect of the percipient). While only the craftsman possesses the material and efficiency to render the form substantially, thereby actualizing it in matter, anyone who recognizes the chandelier as such participates the formal cause with his intellection, thereby actualizing it in mind.

Lastly, the final cause (causa finalis, or τέλος) is that “for which” a thing tends, as an acorn tends towards an oak, or that “for which” a thing is made, like a bell for ringing or a chandelier for swinging, and so on. In living things, formal, final, and efficient causes are often indistinguishable. They are generally immanent to, and not imposed on, the entity in question. For instance, the acorn grows into the oak by a design, goal, and power, which are inherent to its being an acorn. An acorn that did not do these things would not be one. Artefacts, by contrast, depend on an outside agent to impart the formal and final causes into the material cause by means of the efficient one. Thus, planks and beams depend on a carpenter if they are to become a bed.12

Bacon, Philosophical Works of Francis Bacon, 95

Bacon, Instauratio magna, 267

Plato, Phaedo 98b-99b

Please consult the appendix above for more on this topic, as well on an explication of the Aristotelian paradigm of explanation that Bacon is opposing.

Hart, “Where the Consonance Between Science and Religion Lies,” December 11, 2020

https://churchlifejournal.nd.edu/articles/where-the-consonance-really-lies/

“pseudo-empirical” because bona-fide empiricism would be indistinguishable from phenomenology, which the paradigmatic scientific method certainly is not

Bacon, Instauratio, 303

This reconception of physics provides for the substitution of “laws” and their subordinate “clauses” to govern from without, those relations which were once inherent to the phenomena in question. Bacon obviously envisioned nature by analogy to a civil state, the behaviour of whose subjects which could be predicted and controlled by understanding the “laws” and subordinate “clauses” that governed them. Bacon was not himself a scientist, but a lawyer by profession, and therefore the mathematical legislation of Nature was left to his contemporaries.

The following is a gloss on Aristotle’s texts, especially Nichomachean Ethics, Da Caelo, Physics, and Metaphysics, the understanding of which I am greatly indebted to Latin translations and commentaries by Thomas Aquinas, which various scholars have also translated into English. To triangulate the meaning of a difficult passage between three languages is of immense assistance.

Most notably, biology, which in its peremptory exclusion of teleology from its theories, establishes itself as a study of life (bios) without the principle of life (i.e., teleology, or immanent causation) and thus a contradiction in terms.

My own laborious translation of “εἶδος δὲ λέγω τὸ τί ἦν εἶναι ἑκάστου καὶ τὴν πρώτην οὐσίαν,” Metaphysics, 1032b.

For Aristotle, while metaphysics, which he referred to as “first philosophy” was the study of being qua being (το όν ή όλ), physics, from the Greek φύσις (physis), was the study of beings, in their generation, motion, and corruption. Nowhere in the corpus Aristotelicum does the word “metaphysics” appear. The word was original with later commentators, and likely derived from the conventional Hellenistic sequence in which Aristotle’s books were ordered. Meta in this case refers to its being subsequent to the “Physics.” The double-entendre of the prefix fits naturally with the thematic relation between the two works and likely accounts for the title’s persistence even without attestation from The Philosopher.

I am very glad that you have written an essay on types of causation other than efficient cause. I have some thoughts of my own.

1.) It is important to remember that the Neoplatonic philosophers had six types of causation. In addition to the four Aristotlean causes they posited paradigmatic cause and instrumental cause. Instrumental cause is easy enough to comprehend, it is the means or instrument by which a cause brings about effect. Paradigmatic cause is posited in The Timaeus and expounded upon by Proclus. That’s a little harder to comprehend. The oversimplified version is that there a paradigm of resemblances that is prior to forms. That resemblances are crucial for connections of things to another.

2.) I absolutely agree that the purging of formal, paradigmatic, material, instrumental, and final cause does leave us with an impoverished view of nature. That there is more than just efficient cause.

But the flip side is that these notions of more-than-just-efficient cause desperately need to be restored in Christian theology. Especially in apologetics. So that an argument for the existence of God on the basis of first efficient cause will be invalid. So we should instead argue for the existence of God on the basis of first formal cause and first paradigmatic cause. That we should not confuse final cause with the cause and effect of science and engineering.

This, I think, is also crucial for understanding the issue of evolution. In terms of efficient cause one species can and has evolved from one to another. In terms of efficient cause, humans have indeed evolved from apes. In terms of formal cause, however; no, the form of ape does not inhere on a human being. This is also crucial for understanding the creation itself. In terms of material cause, the universe is from nothing. In terms of instrumental cause, it is by God. In terms of formal cause, the creation is from God. In terms of paradigmatic cause, the creation is in God. In terms of final cause, it is to God.

Again, I deeply appreciate that you have brought this up, and I hope that others follow suit.

There is important evidence that indicates that when Earth evolution began, the Physical Body Archetype, first formed on Saturn, and then further developed on Sun, when the Etheric Body was formed, and then further elaborated on Moon, when the Astral Body was formed, stood at the outset of Its fourth formation, or Physical Phantom Body. And, Earth evolution was intending in this direction as outlined here:

https://rsarchive.org/Lectures/GA233a/English/RSP1965/19240111p01.html

So, in the description of the original Seven Days of Creation, described in Genesis 1, we have this Physical Phantom evolving as the Fourth Hierarchy, and wherein Man is deemed Lord of the Earth. Thus, pure spiritual perception was the design of the first seven days of creation. Then, the Lord God comes on the scene, beginning with Genesis 2:4, and everything changes. The "fall of man" occurs at this point, and Earth evolution shifts from a Geocentric model to a Heliocentric model, which is governed by Jahve/Christ ever since. The original design of Physical Phantom as the Fourth Hierarchy becomes sublimated to the 10th Hierarchy, and eventually needing Christ to incarnate on Earth for the redemption of the Resurrection Body (Physical Phantom) through the Mystery of Golgotha. The key is the necessity of the occurrence of the so-called, "Fall of Man", and wherein the dust of the earth becomes the forming agent, and the Lord God breathes life into his nostrils, and he becomes a living soul. Thus, Earth evolution became the evolution of the human soul in further elaborating the physical, etheric, and astral bodies, into Sentient Soul, Intellectual Soul, and Consciousness Soul. This eventually forces the awakening of the "I Am", which Moses had personally experienced, and now becomes the common property of Humanity in this Consciousness Soul Age.