Metanoia in the Book of Job

Below is an excerpt from an article published today in VoegelinView on suffering and the transformative power of “repentance,” properly conceived, as it is expressed in the Book of Job.

The story of Job is at once ancient and immediate to us. Thousands of years divide us from the primaeval setting of this story, and yet we encounter its strange protagonist with a sense of intimate familiarity. We may even see our own likeness in Job and his trials—who has not had his faith tested in the furnaces of hardship? Unlike the brawny and heroic figures that Homer presents in the likes of Achilles and Odysseus, The Book of Job puts on display all of the frailty of the human condition. And yet, Job also shows us the manner in which these trials by fire may become more than mere sources of suffering or woe. Instead, they can become catalysts for inner transformation. The same forge that melts the iron may also temper it. Indeed, transformation implies a dissolution of a prior form as a condition to establish the new one.

I wish to briefly explore The Book of Job as something like a roadmap of “repentance.” Just like the story itself, the word “repentance” conceals its true meaning by appearing as such. Often “repentance” evokes associations with “regret” and “remorse.” Thus the significance of the term is hid under the bushel of a familiar word. But “repentance” is an esoteric name for an inner transformation. It may be conceived as “intellectual conversion,” or “revolution of the spirit,” or “turning about of the heart,” or “going beyond the mind,” etc. “Repentance” appears as a conventional translation of the very expressive Greek term metanoia (μετάνοια, μετά- “above,” “about,” “over,” “after” + νοια “mind,” “intellect,” “spirit”), which evokes the image of interior conversion. Thus, The Book of Job is a manual of metanoia.

Conventional interpretations of The Book of Job have tended to lay emphasis on the literal and theological dimensions of the text. More specifically, the story of Job is interpreted as the depiction of a righteous man, which others may emulate. The Epistle of James, for instance, affirms that “we count them happy which endure” and then puts forth Job as an exemplar: “Ye have heard of the patience of Job.” (James 5:11) Job is confronted with a trial that tests his faith. He overcomes the trial and God compensates him for his trouble: “also the LORD gave Job twice as much as he had before.” (Job 42:10) In this way, the story may serve to incentivise taking Job as a role model for the sake of guaranteeing a reward for ourselves. Interpreted in this way, the story may also seem to affirm the very principle of cosmic justice or karma that God’s speech from the whirlwind in the climax of the narrative nominally appeared to contradict. This is as awkward a reading as it is common, however, because not only do God’s deeds and testimony call into question that the world that he created and seems to minister is fair, but Job’s own speeches hardly strike one as the words of a paragon of unwavering faith and stoic endurance. If anything, The Book of Job recounts how Job’s stoicism is dashed on the rocks of anguish. “Naked came I out of my mother’s womb, and naked shall I return thither: the LORD giveth, the LORD taketh away, blessed be the name of the LORD” (1:21) gives way to a jeremiad two chapters later; like a dam that is burst by torrents of woe. Job begins his lament by cursing the day he was born, (3:3) and over the course of his replies, repeatedly accuses God of injustice (10:1-7, 12:6, etc.), demanding that God give an account and defence of his persecution, though at the same time affirming that God is unbeholden to this demand, “For he is not a man, as I am, that I might answer him, that we should come to trial together.” (9:32) Suffice it to say that these statements hardly resemble the virtues that we typically ascribe to Job. At the same time, Job also seems to possess the mustard-seed of redemptive faith: “For I know that my redeemer liveth, and that he shall stand at the latter day upon the earth: And though after my skin worms destroy this body, yet in my flesh shall I see God.” (Job 19:25-26)

Job’s words are prophetic in the context of the narrative since he foretells his encounter with God at the end of the text. They are also prophetic in the context of the revelation of the New Testament since they affirm Jesus’ assertion that “…he that hath, to him shall be given: and he that hath not, from him shall be taken even that which he hath.” (Matthew 4:25) Still, Job’s soul is by no measure unanimous in the conviction of its eventual salvation and indeed, the bulk of the narrative concerns itself with Job’s trials and Job’s doubt and not his faith. Perceiving this discrepancy is what led me to inquire further into the meaning of the story of Job, and I will present some conclusions later in this exploration. First, however, I wish to touch on another theme that is conventionally coupled with this ancient text. This is of course the problem of evil, or theodicy.

The Greek philosopher Epicurus offered among the most concise articulations of this basic challenge to classical monotheistic worldviews:

Is God willing to prevent evil, but not able? Then he is not omnipotent.

Is he able, but not willing? Then he is malevolent.

Is he both able and willing? Then whence cometh evil?

Is he neither able nor willing? Then why call him God?

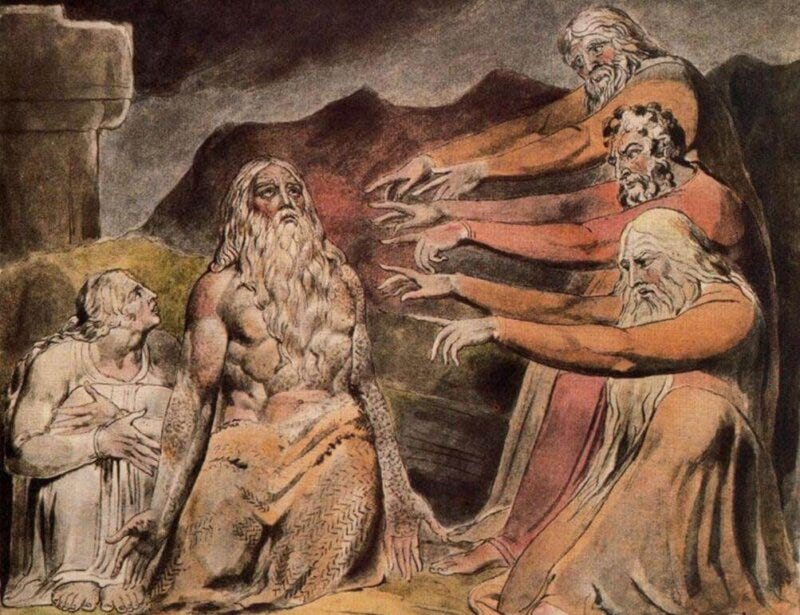

The interlocutors in The Book of Job pose a similar dilemma. If God is just, and if Job is pious, why then does Job suffer? Eliphas, Bildad, and Zophar affirm the antecedent as an axiom and are forced to deny Job’s piety “Doth God pervert judgment? or doth the Almighty pervert justice?” (8:3)

Should thy lies make men hold their peace? and when thou mockest, shall no man make thee ashamed? For thou hast said, My doctrine is pure, and I am clean in thine eyes. But oh that God would speak, and open his lips against thee; And that he would shew thee the secrets of wisdom, that they are double to that which is! Know therefore that God exacteth of thee less than thine iniquity deserveth. (11:3-6)

Job, by contrast, retains unfaltering conviction of his own innocence and as a result doubts that God has dealt justly with him. For this reason, he demands that God give an account for the reason of his afflictions. As I noted above, the true object of Job’s faith appears to be in his own lack of sin and not in God’s fairness. “Thou knowest that I am not wicked; and there is none that can deliver out of thine hand” (10:7), “Behold now, I have prepared my case; I know that I will be vindicated” (13:18) while “The tabernacles of robbers prosper, and they that provoke God are secure; into whose hand God bringeth abundantly.” (12:6)

How does The Book of Job seem to answer the challenge of theodicy?…Continued at VoegelinView.