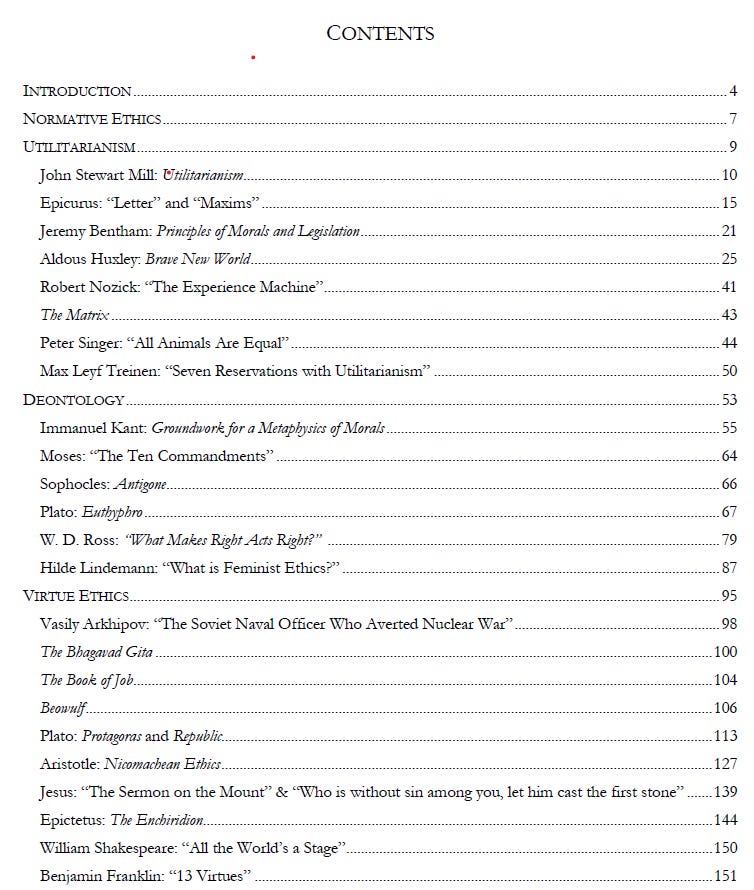

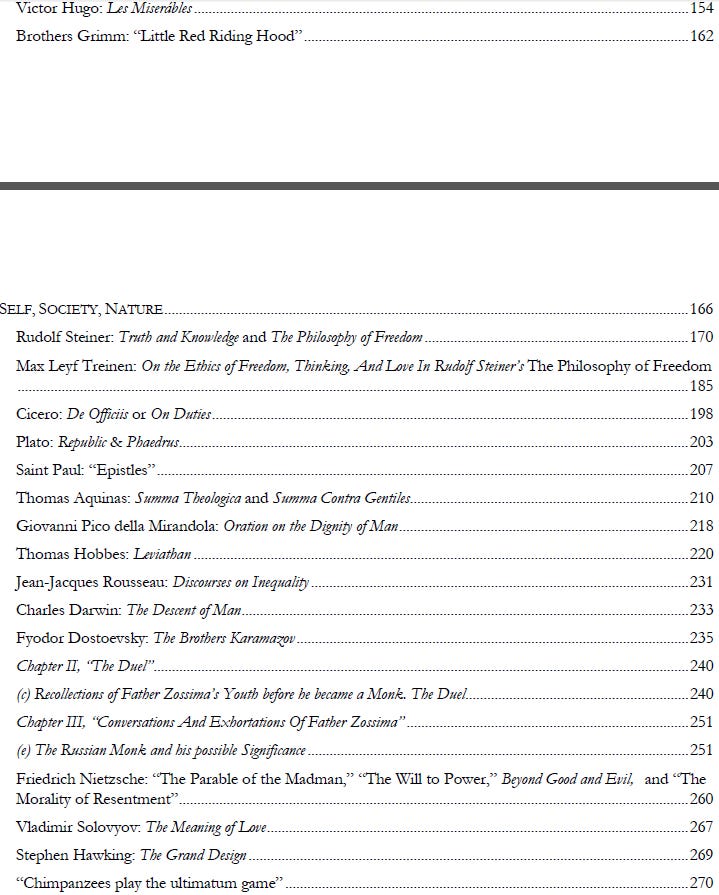

After having taught an Ethics course at Alaska Pacific University for a number of years, and now at the University of Alaska Anchorage as well, I have found myself sufficiently dissatisfied with the commonly available textbooks and ethics readers to write my own. Whether it will end up as anything more than a personal reference and teaching tool is neither here nor there because my purpose in composing it is my conviction that it will serve the education of my students and I have already been employing it to that effect for two years now. Anyone with interest is welcome to request the whole compilation as a PDF, for which I have included the table of contents below.

Utilitarianism has a straightforward and immediate appeal to many people; after all, why wouldn’t we wish to reduce suffering and maximise pleasure? But in fact, there are a number of reasons to harbor reservations against the utilitarian doctrine. These include, but are not limited to, seven of which I will attempt to present below.

First, pace Bentham, an objective hedonistic calculus may be impossible. Psychological states are qualitative realities that cannot be directly translated to quantitative values. How does one measure the quantum of happiness that accompanies the smell of cinnamon? And even were it possible to achieve such a measurement, there is no way to generalize this result because each successive encounter with the same phenomenon will, as a rule, invoke different psychological responses in the same individual according to diverse contexts. This problem is complicated by orders of magnitude when considering more significant experiences like friendship, childbirth, or marriage.

Second, even if the first difficulty were adequately resolved, one would, once again, encounter an inherent difficulty if not impossibility in generalizing between individuals. Given that the utilitarian ideal is the augmentation of net happiness, it is necessary to obtain an objective and quantitative measure that is commensurate between various individuals. How can it be established that my capacity for happiness is comparable to that of my fellow? One may attempt to correlate the psychological experiences of pleasure and pain to given brain states, but this is not an adequate solution unless we are prepared to substantially reimagine the fundamental principles of utilitarianism such that it is no longer a question of promoting happiness and mitigating its inverse but rather one of fostering the propagation of specific brain states. What the latter would gain in respect to measurability it would forfeit in respect to intelligibility and intuitive appeal. And the utilitarian doctrine was supposed to be an ethical doctrine and not a physiological one.

Third, the fundamental maxim of utilitarianism—the greatest happiness for the greatest number—is conceptually indeterminate and has no definite denotation. How do we determine that criteria to be included in the utilitarian calculus? How widely do we cast our nets? To the family? The tribe? The nation? The species? The phylum? The kingdom? The planet? The stars? “The greatest happiness for the greatest number” is so abstract in theory as to be almost meaningless in application.

Fourth, “the greatest happiness for the greatest number” is historically indeterminate and, again, possess no definite denotation. Even if it were possible to establish the scope of application of utilitarianism in principle and thereby satisfy the objection above from point 3, the scope in time would remain unspecified. Are we to consider the greatest good for the greatest number with an outlook that extends into the next minute? The next hour? The next year? The next generations? The fullness of time?

Fifth, consequentialism might not represent an altogether actionable ethical theory. This objection relates to the difficulty established in the prior one: namely, how are we to establish the rightness or wrongness of a given action on the basis of an outcome that does not yet exist? It seems unreasonable to judge a given deed against a standard that is, at best, conjectural and in many cases even counterfactual. Most theories of ethics do not encounter this difficulty because they do not attempt to conceptualize human actions entirely from the outside, as it were. This is to say that most theories of ethics do not attempt to abstract a given action from the motives, intentions, and character of the agent who is carrying it out. The physics of an acorn falling from a tree can be, to a large extent, described without appeal to the internal disposition of the tree. Hence, we do not ordinarily call this an “action” but an “event.” Utilitarianism risks dissolving this distinction with the result that it ceases to be describing a theory of ethics at all because events are not the same thing as actions.

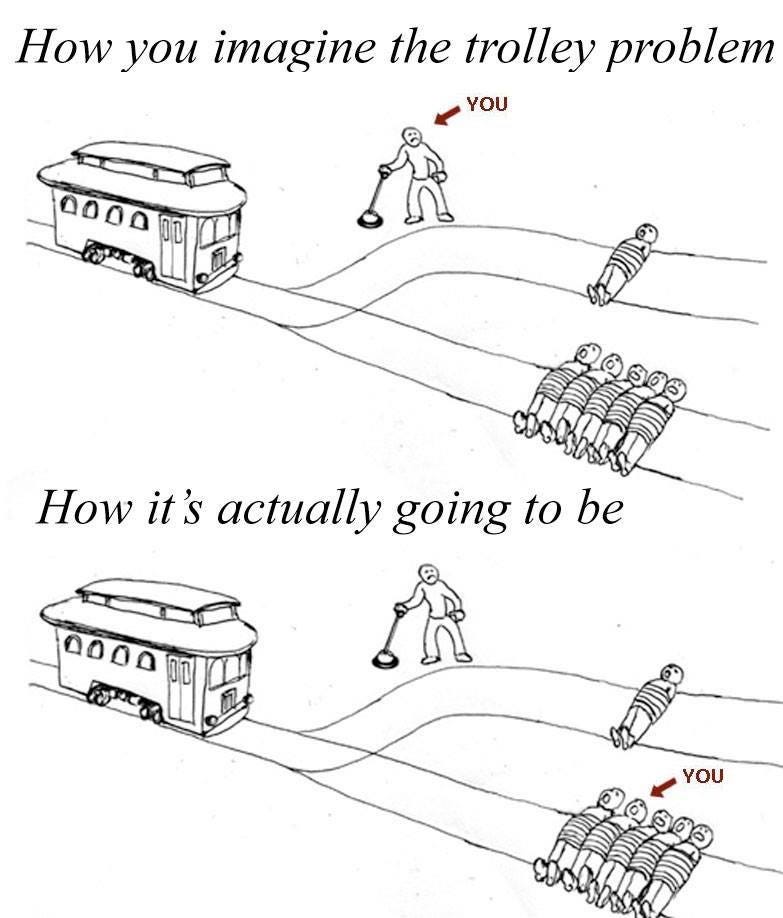

Sixth, utilitarianism seems to encourage the scapegoat mechanism in which the interests of the minority are sacrificed for the sake of the majority. Utilitarianism, in attempting to subvert individual interests in the pursuit of the ideal of objectivity, risks losing touch with the only experience of reality that actually exists: viz. each of our perspectives. There is no such thing as happiness in the abstract outside of the experience of happiness, which is contingent on the subjectivity of individual beings. A fortiori, to issue ethical judgements on the basis of a “view-from-nowhere”—which is a view that nobody inhabits and hence which does not exist—may represent an impossible notion that people only appear to accomplish through affectation.

Seventh, and finally, utilitarianism might not be a theory of ethics at all. The combined force of the objections above threaten the conclusion that utilitarianism might fail to represent a bona fide theory of ethics. Naturally, the judgement over this question will hang on what is understood by the term. There is reason, however, to demand from an ethical theory that it supply some guidance to our actions and help us orient our lives towards what is good. Practically, utilitarianism leaves so many elements of its imperatives undefined and indeterminate that it appears to be able to justify almost anything and, insofar as this is true, the guidance that it is capable of providing is worth next to nothing. An ethical theory that can only definitively recommend a course of action after that same action has already been performed and which, moreover, may not even be capable of measuring the worth of this action according to its own criterion, might appear be an ethical theory that is in need of improvement. And even if this difficulty were resolved, one might yet be inclined to demand more of such a theory than an evaluation of specific action according to a standard that that very theory set forth: “Or do you think it is such a small thing to decide on a way of living?”1

Plato’s Socrates to Thrasymachus, in Republic, Book 1, 344d-e.

It’s probably just me. We’re still friends.😉 no worries

That one didn’t seem to sit as nicely as the other ones. Lol seems that’s quite a bit of judgment. Although it seems you have figured it out nicely some of us just try the best we can.