education as liberation: learning as “a turning of the soul”

Government cannot make people free; only education can do that

—Rudolf Steiner, 1884

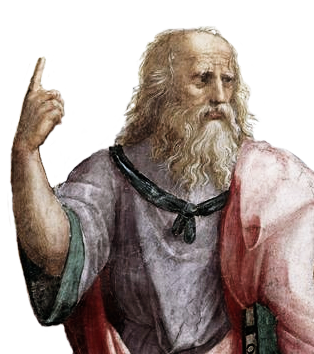

What is the purpose of education? It is possible to propose a thousand answers to this question ranging from the most material to the most sublime. Perhaps it is to render myself more attractive to employers. Perhaps it is for prestige. Perhaps it is to render myself capable of contributing to society. I would like to explore a traditional answer to this question without necessarily rejecting any one of the answers that people are wont to venture. Indeed, I think I can show how the answer that I will attempt to lay out actually affirms all of them by integrating them into a larger whole, just as my thumb becomes more itself the more it is a part of me, and were it parted from me, would ultimately cease to be a thumb at all. Since Plato’s day, Philosophers have affirmed that the purpose of education is to make us more free. Seneca, for instance, observers:

You see why the liberal arts have their name: they are worthy of a free person. But there is only one true liberal discipline, the study that makes you free. This is the study of wisdom, it is sublime, bold, and filled with a greatness of spirit.1

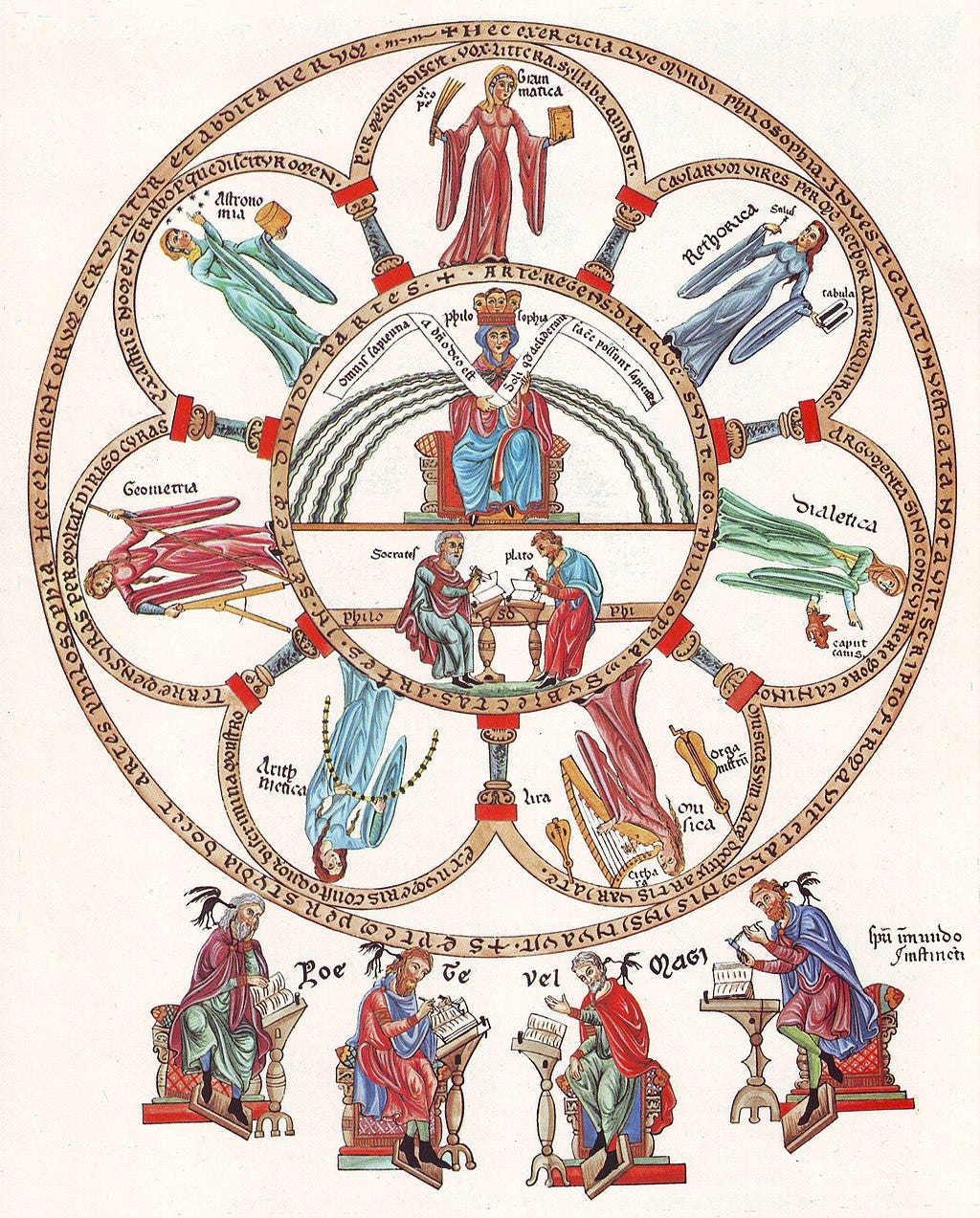

Perhaps the quintessential argument for this view remains, to this day, Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave.” To this iconic parable can be added the fact that the original university curriculum consisted in a study of the septem artes liberales, or the “seven liberal arts,” and of course, the assertion is explicitly stated in the quote above.

Hence, we may be tempted to exclaim: “the purpose of education is to make us free,” and triumphantly close the book, pull down the shutters, and terminate the inquiry. But an answer that is not understood is no answer at all, but a new question: something cannot be an answer to me if I don’t know what it means. Indeed, a person could probably provoke ChatGPT to say that, with the right prompting. But to treat anything that might eventually issue out of ChatGPT as an answer in its own right would be a category mistake. It would be as if someone were to say, “I see a vertical line and a diagonal line and another vertical one, and then a circle,” whereas in fact he should merely read the word “No.”

The situation is comparable to the task of science: all of the essential forces, powers, and energies of existence are already present in a mustard seed, or a grain of sand. But it does no good for a physicist to hold up a mustard seed and say, “see?” except to the one who can already see this.2 Until then, it only poses a further question.

Hence, before the original question of education’s purpose we must pose a preliminary one: what does it mean to understand? In the spirit of Plato, I wish to show before I attempt to tell:

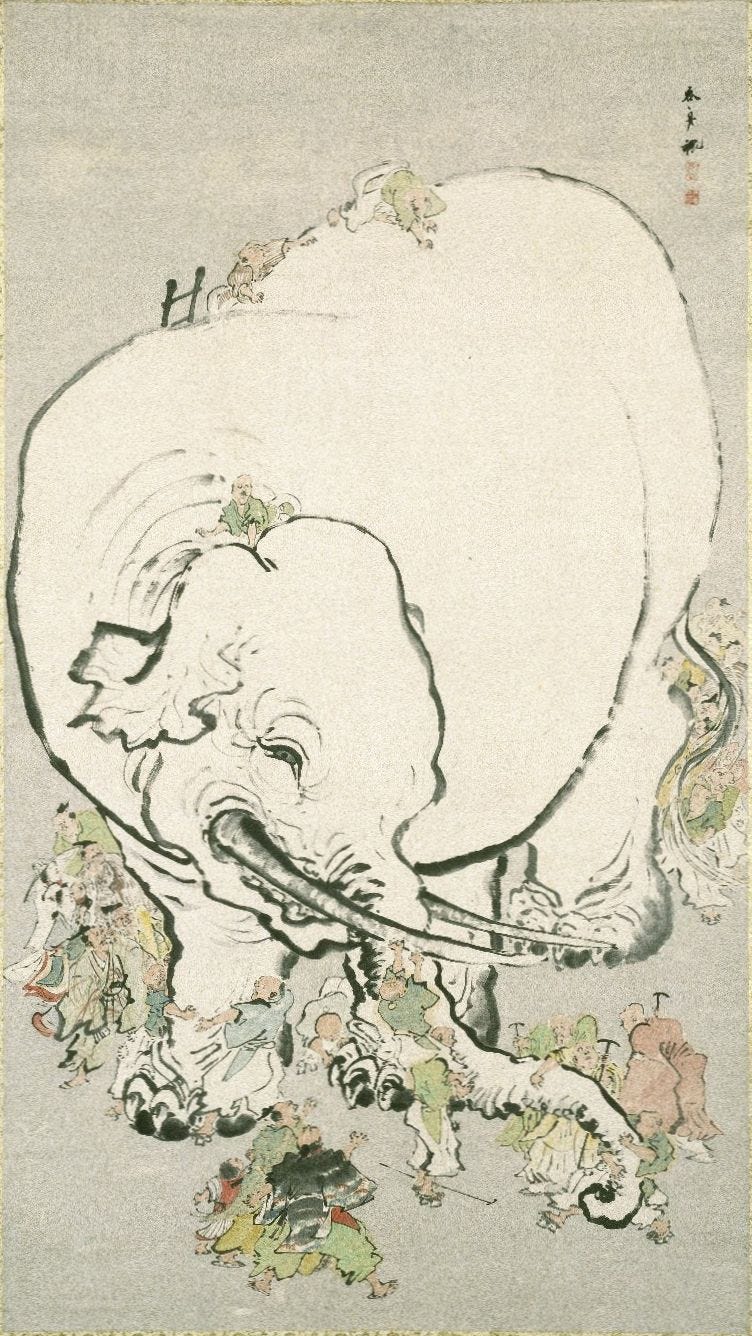

IT was six men of Indostan To learning much inclined, Who went to see the Elephant (Though all of them were blind), That each by observation Might satisfy his mind. The First approached the Elephant, And happening to fall Against his broad and sturdy side, At once began to bawl: "God bless me!—but the Elephant Is very like a wall!" The Second, feeling of the tusk, Cried: "Ho!—what have we here So very round and smooth and sharp? To me 't is mighty clear This wonder of an Elephant Is very like a spear!" The Third approached the animal, And happening to take The squirming trunk within his hands, Thus boldly up and spake: "I see," quoth he, "the Elephant Is very like a snake!" The Fourth reached out his eager hand, And felt about the knee. "What most this wondrous beast is like Is mighty plain," quoth he; "'T is clear enough the Elephant Is very like a tree!" The Fifth, who chanced to touch the ear, Said: "E'en the blindest man Can tell what this resembles most; Deny the fact who can, This marvel of an Elephant Is very like a fan!" The Sixth no sooner had begun About the beast to grope, Than, seizing on the swinging tail That fell within his scope, "I see," quoth he, "the Elephant Is very like a rope!"

It’s the traditional parable of “The Blind Men and the Elephant,” in John Godfrey Saxe’s telling. The blind men illustrate what it means to fail at understanding. To understand is to see through one’s standpoint to the higher idea. To understand means to grasp the whole through the parts. To understand is to grasp the spirit through the letter, and in this way, it is in every way comparable to reading. Indeed, it is a form of lectio: intellectio. To begin with, each blindman was bound to his particular standpoint. To understand, he would have to be freed from his particular standpoint to compass the whole of the elephant. Seen in this way, understanding is a kind of freedom; a freedom from the tyranny of our own standpoints, our own past thought, our own inherited prejudices and preconceptions.

Now it can be seen how what perhaps seemed to be two questions have been in fact one. In other words, by learning what it is to understand, we have also begun to grasp what it is to be free. Now let us turn to Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave,” which encompasses the “Parable of the Blind Men” but carries it further. Since we are born, people are telling us how to see and as a result, we form certain opinions about the way things are. This risks holding us captive if we are not willing to hold these beliefs up to critical scrutiny. As Descartes said, to be free from all inherited prejudice, the only thing needful is doubt.

“The Allegory of the Cave” represents, in visible images, phenomena that are invisible; phenomena that we ordinarily see through but which we do not at first see. The “Allegory of the Cave” is of course a symbol of philosophy, “the love of wisdom.” For the prisoner in Plato’s allegory to turn and move himself represents a new power or faculty of the mind or soul that is different from the one by which we passively and inertly behold phenomena in a dreamlike way. What does it mean, “dreamlike”?

One hallmark of a dream-state is to not understand the causes of perceptions. Suppose, for instance, that your house is on fire. To begin with, you will attempt to extinguish the fire, and then you may wish to seek out the probable cause and, if it were arson, then to prosecute the offender etc. But when you recognize the dream, you no longer seek to prosecute an arson but instead you open the window. The faculty by which we understand the cause of perceptions is the same faculty by which we grasp the wholeness of the elephant and it is, again, the same faculty by which we undertake our “steep and rugged ascent” from Plato’s Cave.

A second feature of the dream-condition is to be born along passively by experience, merely seeking to attain what we semiconsciously desire and flee from what we semiconsciously fear or despise. To awaken is not to go to some other place, but to change one’s state; to become intentional in our lives. We cease to be passengers and become the captains and crews. We cease to be characters in our own biographies and become the authors of them.

Imagine, then, if you will, a revision of Plato’s allegory in which the figures on the cave wall were our own shadows, only we did not know our own movements in them. As long as I only stare intently at the shadows, even were I to bring to bear all of the fruits of scientific methodology, my apparent knowledge will only increase my delusion. The only way to see an effect in its reality is to know its cause. The only way to see shadows in their reality is to index their movements to the activity of my own limbs and body. Similarly, the only way to see the latter correctly is to index them to intentions of my mind that fire my limbs with will. To begin with, we are prisoners in this way, but education makes us free. As you are learning things, all along you are also learning how to learn. This is a higher wakefulness than that of merely having learned things. In this way, as you proceed in your education, you are simultaneously coordinating and exercising the limbs of your spirit.

We think to be free means “to be able to do whatever I want.” But freedom from external constraint alone is not sufficient to secure freedom in the positive and creative sense. Anyone who doubts this can imagine driving with a blindfold on, but with nothing and no one to stay your hand, or exercising your democratic “freedom” by casting a ballot for a candidate you’ve never heard of. Anyone is free to become a doctor, a writer, a carpenter, a teacher. But everyone must realize, that is, “make real,” this freedom for himself. Education makes us free to do this. It frees us from “knowingness” and frees us to be knowers. It frees us from past thoughts and frees us to think afresh. It frees us from narrow-mindedness and frees us to see. As the Master sayeth:

And ye shall know the truth, and the truth shall make you free.

“We be Abraham’s seed,” the Pharisees, offended, counter, “and were never in bondage to any man: how sayest thou, Ye shall be made free?”

Verily, verily, I say unto you, Whosoever committeth sin is the servant of sin.3

Freedom then, can never be ours so long as we imagine we already possess it, or that it will merely fall into our laps. Nothing other than ourselves can realize our freedom, not even “the government.” Freedom is not something that can merely be handed to us. It is not knowledge. Instead, it is the capacity that precedes knowledge, and it a capacity we must win for ourselves; a capacity we must develop through exercise, through undertaking the “steep and rugged ascent” that Plato describes. Not only do we learn something in the climb, but we also make something of ourselves. Rudolf Steiner affirms our task:

The plant transforms itself because of the objective natural law inherent in it; the human being remains in an incomplete state unless he takes hold of the material for transformation within him and transforms himself through his own power. Nature makes of man merely a natural being; society makes of him a law-abiding being; only he himself can make of himself a free human being. Nature releases man from her fetters at a definite stage in his development; society carries this development a stage further; he alone can give himself the final polish.4

We should not be troubled if the “ascent,” or the “polish” is difficult or uncomfortable. We perhaps only kindle the fire of freedom through friction with everything that opposes it, and we must stare into the blaze thus created and not avert our eyes. Otherwise we might just roll over in our sleep. The cave-dwellers, turned to the wall of the cave are dreaming, and they are us until we see this: but to know that I am dreaming is already to have turned5 myself and begun to tread the path of awakening. Plato describes the relevant conversion:

our argument shows that the power and capacity of learning exists in the soul already; and that just as the eye was unable to turn from darkness to light without the whole body, so too the instrument of knowledge can only by the movement of the whole soul be turned from the world of becoming into that of Being, and learn by degrees to endure the sight of Being, and of the brightest and best of Being, or in other words, of the Good.6

and concludes that learning is the:

turning the soul from day that is a kind of night, to true Day—the ascent to what is, which is to say, true Philosophy.7

Now it must be said that a waking human is more fully human than a dreaming one just as a tulip is more fully itself as a flower in the light than a bulb in the dark earth, and an oak is more fully itself as a tree than an acorn. Hence, to be more fully awake is to be more fully ourselves.

The argument goes like this: the fully actualized human being is the free human being, and since the purpose of education is to make us more free, the purpose of education is to make us more fully human. I hope it can be seen how this view gathers together, sums up, and integrates all of the prior views in the same way that the comprehension of the elephant gathers together all of the discrete perceptions of its divers features. The power of human freedom flows into each of these proximate purposes and animates them, like glass poured into a mould, or like the will and essence of the elephant flows into each of its limbs and appendages. Just as we can now point to any part of the elephant and say, “this is he,” so we can see the wholeness of our lives through every part of them. In this way, your life no longer remains an accident becomes instead a task, a work of art, what the alchemists, in coded language, designated as the magnum opus, or “Great Work.”

Quare liberalia studia dicta sint, vides; quia homine libero digna sunt. Ceterum unum studium vere liberale est, quod liberum facit. Hoc est sapientiae, sublime, forte, magnanimum.

Seneca, Moral Epistles 88.1-2

Cf. Buddha’s notorious “Flower Sermon.”

John 8:32-34.

Steiner, The Philosophy of Freedom, ch. 9. In a lecture, he elaborates on the same theme:

We may say, therefore, that the insect has a certain direction in its life through spring, summer, autumn and winter. It does not give its development up to chance, placing itself as it does within certain laws in each succeeding phase of its life. Mankind, however, has left behind the age of instinctive co-existence with nature. In his case it was more ensouled than that of the animals, but still instinctive. His life has taken on a newer, more conscious form. Yet we find that man, in spite of his higher soul-life and capacity to think, has given himself over to a more chaotic life. With the dying away of his instincts he has fallen, in a certain way, below the level of the animals. However much one may emphasize man's further steps forward, towering above the animals, one must still concede that he has lost a particular inner direction in his life. This directing quality of his life could be found once more by seeing himself as a member of the human race, of this or that century. And just as, for a lower form of life, the month of September takes its place in the course of the year, so does this or that century take its place in the whole development of our planet. And man needs to be conscious of how his own soul-life should he placed historically in a particular epoch.

Cf. John 20:

14And when she had thus said, she turned herself back, and saw Jesus standing, and knew not that it was Jesus. 15Jesus saith unto her, Woman, why weepest thou? whom seekest thou? She, supposing him to be the gardener, saith unto him, Sir, if thou have borne him hence, tell me where thou hast laid him, and I will take him away. 16Jesus saith unto her, Mary. She turned herself, and saith unto him, Rabboni; which is to say, Master.

Plato, Republic, 518c.

Plato, Republic, 521c.

this is brilliantly written. so many beautiful images. truly, a work of art. thank you.

Your quickly becoming one of my favorite ‘people’. Thank you for being you.