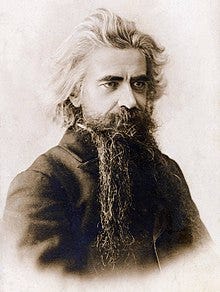

Today is the anniversary of the death of Vladimir Solovyov in 1900. Born in 1853, Solovyov was a Russian philosopher, theologian, poet, and mystic. He was a seminal figure in the school of sophiology, which is a poly-synthesis of Platonic and Christian idealism with the inherently mysterious feminine aspect of divinity, particularly in connection with Creation and the natural world. The latter is often referred to as “Wisdom,” “Sophia,”1 or “Shekhinah.”2 In the selection below, excerpted from Solovyov’s 1891 work, The Meaning of Love,3 the philosopher, clearly drawing on Diotima’s famous “ladder of love” as presented in Plato’s Symposium,4 outlines an extraordinary theory and exegesis of love as the principle of transcendence as such. The work as a whole presents a fascinating argument for a teleological interpretation of Darwinian evolution in which the apparent “descent of man” is, viewed from the inside, an involution of spirit into matter and an evolution of species in capacity and dimensions of love.

From The Meaning of Love:

…The matter of true love is above all based on faith. The root meaning of love, as has already been shown, consists in the acknowledgment of absolute significance for another being. But this being in its empirical being, as the subject of real sensuous perception, does not have absolute significance: it is imperfect in its worth and transient as to its existence. Consequently, we can assert absolute significance for it only by faith, which is the assurance of things hoped for, the conviction of things not seen. But to what does faith relate in the present instance? What does it strictly mean to believe in the absolute, and, what is the same thing, everlasting significance of this individual person? To assert that he himself, as such, in his particularity and separateness, possesses absolute significance would be as absurd as it is blasphemous. Of course the word “worship” is very generally used in the sphere of amorous relations, but then the word “madness” likewise possesses its legitimate application in this domain. So then, observing the law of logic, which does not allow us to admit contradictory definitions, and likewise obeying the command of true religion, which forbids the worship of idols, we must, by faith in the object of our love, understand the affirmation of this object as it exists in God, and as in this sense possessing everlasting significance. It must be understood that this transcendental relation to one’s other, this mental transference of it into the sphere of the Divine, presupposes the same relation to oneself, the same transference and affirmation of oneself in the sphere of the absolute. I can only acknowledge the absolute significance of a given person, or believe in him (without which true love is impossible), by affirming him in God, and consequently by belief in God Himself, and in myself, as possessing in God the center and root of my own existence. This triune faith is already a certain internal act, and by this act is laid the first basis of a true union of the man with his other and the restoration in it (or in them) of the image of the triune God. The act of faith, under the real conditions of time and place, is a prayer (in the basic, not in the technical sense of the word). The indivisible union of oneself and another in this relation is the first step towards a real union. In itself this step is small, but without it nothing more advanced or greater is possible.

Seeing that for God, the eternal and indivisible, all is together and at once, all is in one, then to affirm any individual being whatsoever in God signifies to affirm him not in his separateness but in the all, or more accurately—in the unity of the all. But seeing that this individual being, in his given reality, does not enter into the unity of the all, but exists separately as an individualized material phenomenon, then the object of our believing love is necessarily to be distinguished from the empirical object of our instinctive love, though it is also inseparably bound up with it. It is one and the same person in two distinguishable aspects, or in two different spheres of being—the ideal and the real. The first is as yet only an idea. By steadfast, believing and insightful love, however, we know that this idea is not an arbitrary fiction of our own, but that it expresses the truth of the object, only a truth as yet not realized in the sphere of external, real phenomena.5

This true idea of the beloved object, though it shines through the real phenomenon in the instant of love’s intense emotion, is at first manifested in a clearer aspect only as the object of imagination. The concrete form of this imagination, the ideal image in which I clothe the beloved person at the given moment, is of course created by me, but it is not created out of nothing. And the subjectivity of this image as such, i.e., as it manifests itself here and now before the eyes of my soul, by no means proves that it is subjective, i.e., a characteristic of an imaginary object which exists for me alone. If for me, who am myself on this side of the transcendental world, a certain ideal object appears to be only the product of my own imagination, this does not interfere with its full reality in another higher sphere of being. And though our real life is outside this higher sphere, yet our mind is not wholly alien to it, and we can possess a certain abstract comprehension of the laws of its being. And here is the first and basic law: If in our world separate and isolated existence is a fact and an actuality, while unity is only a concept and an idea, then in the higher sphere, on the contrary, reality appertains to the unity, or more accurately, to the unity-of-the-all, while separateness and individualization exist only potentially and subjectively.”

…the experience of faith. This latter is incomparably more difficult than the former, for it is dependent more on internal action than on reception from without. Only by consistent acts of conscious faith do we enter into real correspondence with the realm of the truly-existent, and through it into true correlation with our “other.” Only on this basis can we retain and strengthen in consciousness that absoluteness for us of another person (and consequently also the absoluteness of our union with him) which is immediately and unaccountably revealed in the intense emotion of love, for this emotion of love comes and passes away, but the faith of love abides.”

...

Love is important not as one of our feelings, but as the transfer of all our interest in life from ourselves to another, as the shifting of the very center of our personal lives.

Compare, for instance, The Book of Proverbs 8:30: “Then I [Sophia] was beside Him as a master craftsman; And I was daily His delight, Rejoicing always before Him.”

הניכש, literally “dwelling,” in reference to God. Compare to Plato’s concept of Khôra (χώρα), from his Timaeus dialogue, translated as “receptacle”:

So likewise it is right that the substance which is to be fitted to receive frequently over its whole extent the copies of all things intelligible and eternal should itself, of its own nature, be void of all the forms. Wherefore, let us not speak of her that is the Mother and Receptacle of this generated world, which is perceptible by sight and all the senses, by the name of earth or air or fire or water, or any aggregates or constituents thereof: rather, if we describe her as a Kind invisible and unshaped, all-receptive, and in some most perplexing and most baffling way partaking of the intelligible, we shall describe her truly. (51a)

Originally published in 1891. First published in English in 1945.

Cf. Symposium, 211a-b.

Cf. Rudolf Steiner, in The Philosophy of Freedom, chapter one:

The way to the heart is through the head. Love is no exception. Whenever it is not merely the expression of bare sexual instinct, it depends on the mental picture we form of the loved one. And the more idealistic these mental pictures are, just so much the more blessed is our love. Here too, thought is the father of feeling. It is said that love makes us blind to the failings of the loved one. But this can be expressed the other way round, namely, that it is just for the good qualities that love opens the eyes. Many pass by these good qualities without noticing them. One, however, perceives them, and just because he does, love awakens in his soul.

“The Russian nihilists have a sort of syllogism of their own — man is descended from a monkey, consequently we shall love one another.”

—Vladimir Solovyov