I wished to share this article that was recently published by my friend Paul Krause in the VoegelinView on the poets’ place in Plato’s Republic. Socrates’ statement in 607-608 seems to suggest that he is calling for them to be expelled, but I don’t think that’s right, for the reasons that I try to lay out in the article, the first part of which is reproduced below. The rest can be read at VoegelinView and it is not behind a paywall or anything.

“Beauty is a manifestation of Nature’s secret laws, which would otherwise remain forever hidden.”

—J. W. von Goethe[1]

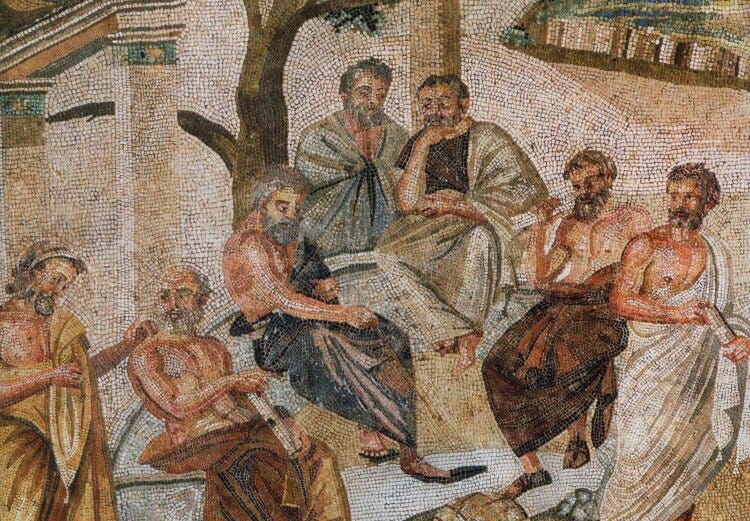

Socrates notoriously advocated for the expulsion of the poets from the Res publica on several occasions in what is perhaps the best known of all of Plato’s some three dozen dialogues. Such a verdict might seem to suggest that art, in the estimation of Socrates, and by extension Plato himself, is of little value in the spiritual ascent towards the vision of the absolute Good.[2] Indeed, for Socrates and Plato alike, Philosophy was far more than we are wont to think of it today. Philosophy for these two was far more than a day-job for academicians or a handmaiden of the sciences. Philosophy, for Plato, was not a discipline, but a Way, and all study was for the sake of transforming the soul to prepare it for a participation in the Good-beyond-Being:

Or do you suppose there is any way in which someone can consort with what he admires without becoming like it? … Then the philosopher, consorting with what is divine and orderly, becomes as orderly and divine as is possible for a man.[3]

Plato’s decision that artists should have no place in the ideal city, therefore, cannot be grasped except in this overarching context. The verdict is meant, therefore, to be taken very seriously. For let it be noted that Republic is not, in fact, foremost a manual for preparing the architectonics of a utopian state at all. Instead, the Republic dialogue is an exploration into the proper order of the soul: “For it is no ordinary matter that we are discussing, but the right conduct of life.”[4] That the order of the soul is the proper subject matter of the dialogue is stated explicitly in Book 2, though admittedly it is easy to overlook since it appears early and is followed by a lengthy conceit that does not expressly indicate its import. “Let us,” Socrates suggests, “[in our inquiry after the idea of justice], employ a method such as nearsighted persons should use if bidden to read small letters from a distance…let us first look for its [justice’s] quality in states, and then only examine it also in the individual, looking for the likeness of the greater in the form of the less.”[5]

What does it mean, then, to “expel the poets from the ideal city,” especially since “the city” is to be understood as an analogue of the soul, and what light can this question shed on the value of art in the soul’s evolution? I will begin my attempt to take up these questions by examining in slightly more detail Plato’s reasons for advocating against the presence of artists in the ideal city. Plato levels three different arguments for his position. The first argument proceeds from an inquiry into the nature of art as such and is therefore substantiated on a metaphysical basis. The second and third arguments proceed from an inquiry into the effect that art has upon people and are therefore substantiated on a consequentialist basis. I will briefly explain each of these arguments in turn.

Please continue reading at the VoegelinView.

[1] Goethe, “Sprüche in Prosa”, in: Goethes Naturwissenschaftliche Schriften, ed. Rudolf Steiner, reprint Dornach 1975, vol. V, p. 495.

[2] Cf. Plato, Republic, 508e:

This reality, then, that gives their truth to the objects of knowledge and the power of knowing to the knower, you must say is the idea of the Good, and you must conceive it as being the cause of knowledge, and of truth in so far as known. Yet fair as they both are, knowledge and truth, in supposing it to be something fairer still than these you will think rightly of it. But as for knowledge and truth, even as in our illustration it is right to deem light and vision sunlike (ἡλιοειδῆ), but never to think that they are the sun, so here it is right to consider these two their counterparts, as being like the good or boniform, but to think that either of them is the good is not right.

[3] Plato, Republic, 500c.

[4] Plato, Republic, 352d.

[5] Plato, Republic, 368d-369a.