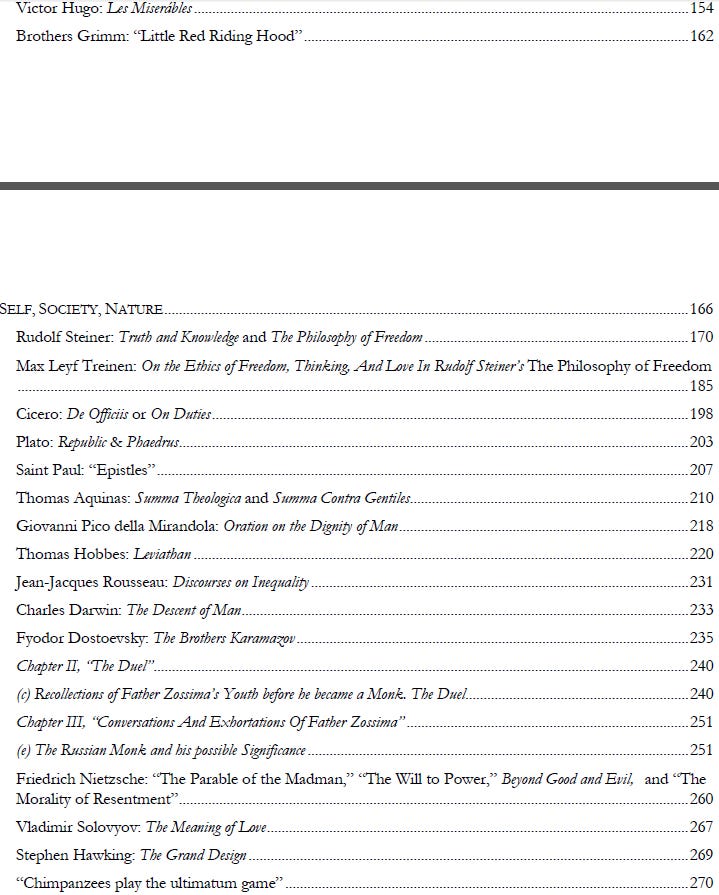

After having taught an Ethics course at Alaska Pacific University for a number of years, and now at the University of Alaska Anchorage as well, I have found myself sufficiently dissatisfied with the commonly available textbooks and ethics readers to write my own. Whether it will end up as anything more than a personal reference and teaching tool is neither here nor there because my purpose in composing it is my conviction that it will serve the education of my students and I have already been employing it to that effect for two years now. Anyone with interest is welcome to request the whole compilation as a PDF, for which I have included the table of contents below.

Whereas utilitarianism, at least in its classical formulation, presents a strictly consequentialist approach to ethics, deontology offers a very different view. Unlike consequentialism, which measures the moral worth of an action by the fruits that follow from it, deontology considers only the action itself. As noted in the prior chapter, an “action” which represents the visible expression of an invisible motive, is to be distinguished from an “event,” which does not and for which a purely factual description is ordinarily sufficient. Deontology concerns itself strictly with actions and indeed, the scope of deontology does not extend to the point at which an action can be treated as an event, as is the standard approach of utilitarianism. Deontology makes actions—and the motives of which they are expressions—into its exclusive concern and thus can be starkly contrasted with utilitarianism, and also with the broader category of teleology in ethics altogether. This is because, in a crucial sense, in the deontological conception of ethics, the moral worth of an action is determined before the action is even carried out in full. Teleological ethics, on the other hand, always refers toward some end that is ulterior or transcendent to the action itself. This is implicit in the names of these two categories: “teleology” stems from the Greek word telos (τέλος), which means “end,” while the name “deontology” is derived from the Greek work deon (δέον), which means “duty” or “what is proper.” Thus, while some teleological theories like utilitarianism, which was covered in the preceding chapter, tend to discount the internal motivation of the agent who is performing the given action, for deontological theories of ethics, this internal motivation forms the very crux of the moral question. To judge the moral worth of an act, from a deontological perspective, just is to ask whether the act followed from the proper motive. This leads to the somewhat strange implication that two identical actions with same outcomes could feasibly be evaluated very differently from a moral perspective if the motivations behind them diverged sufficiently. At the same time, most people intuitively recognize the truth of this possibility. That is why if one person gives another person a box on the ear, the event will be interpreted very differently according to whether it was deliberate or not, and even if it was deliberate, whether it was done out of animosity or for the sake of incapacitating an Anopheles mosquito, a bite from which risks infection with malaria. It is also why not every domestic fire is an instance of arson and so on.

A deontological approach to ethics has the advantage over a teleological one in that, from the deontological perspective, the moral value of an action can be determined in an unequivocal way, and not merely in a contingent or conjectural one. Whereas a teleological outlook must generally defer judgment of any given deed to some future time at which its value can be assessed, deontological ethics allows this question to be settled at the very point at which a given motive becomes a deed, and that value is firmly and univocally established—determined solely by the will that impelled it. Immanuel Kant, whose Metaphysics of Morals (1785) will serve as the keynote selection for this chapter on deontology, identifies the constitutive moral value of the good will, and employs it as the cornerstone of his moral philosophy:

Nothing can possibly be conceived in the world, or even out of it, which can be called good, without qualification, except a good will. Intelligence, wit, judgement, and the other talents of the mind, however they may be named, or courage, resolution, perseverance, as qualities of temperament, are undoubtedly good and desirable in many respects; but these gifts of nature may also become extremely bad and mischievous if the will which is to make use of them, and which, therefore, constitutes what is called character, is not good. It is the same with the gifts of fortune. Power, riches, honour, even health, and the general well-being and contentment with one's condition which is called happiness, inspire pride, and often presumption, if there is not a good will to correct the influence of these on the mind, and with this also to rectify the whole principle of acting and adapt it to its end.

Whereas Kant’s approach to deontology takes its departure point from the Enlightenment ideal of ordering life to a perfect system of principles derived directly from Reason, many deontological theories of ethics appeal to other foundations for moral obligation. Many traditional religious codes of ethics, for instance, present prime examples of the deontological approach to ethics. Among the best known of these codes is the Decalogue, more commonly known as “The Ten Commandments,” which Moses is recounted to have received straight from God when he ascended to the top of Mount Sinai and which Moses thus conferred to the Israelites. In this way, the Mosaic Law represents a species of deontology known as divine-command theory. Following this excerpt from the Book of Exodus (circa 7th century BC) is another short excerpt, this one from the tradition of ancient Greek drama. Namely, it is an excerpt from Sophocles’ powerful tragedy Antigone (442 BC). Next follows an excerpt from the dialogues of Plato that was composed within a few decades of Sophocles’ play. This selection from Plato’s Euthryphro (circa 399 BC) presents the notorious “Euthyphro dilemma.” Though the Euthyphro dilemma is, in itself, accidental to the divine-command theory of deontology that the eponymous character in this dialogue presents, the dialogue nevertheless remains a perennial selection for ethics compilations and not without reason. Next is a selection by W. D. Ross in which he outlines a theory of deontological pluralism based on what he calls “prima facie duties.” Unlike Kant’s notorious “categorical imperative,” Ross’ duties are meant to order themselves in relevance in response to any given situation. Finally, I have included an excerpt from Hilde Lindemann’s 2006 book An Invitation to Feminist Ethics in which she outlines a feminist critique of traditional ethics.

On a prior occasion sub umbra coronam, which is, “under the shadow of the Crown,” I have recorded these lectures which are also pertinent to the theme of this piece.