Conscious faith is freedom. Emotional faith is slavery. Mechanical faith is foolishness.

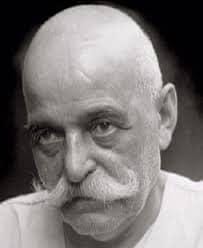

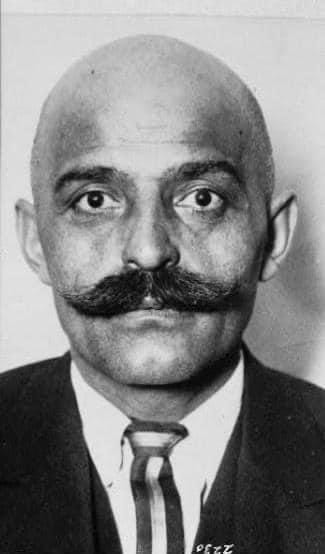

on this day, 1949: George Ivanovich Gurdjieff walked out of life

The evolution of man is the evolution of his consciousness. And “consciousness” cannot evolve unconsciously. The evolution of man is the evolution of his will, and the “will” cannot evolve involuntarily. The evolution of man is the evolution of his power to “do”, and “doing” cannot be the result of what “happens”.

Gurdjieff was a sui generis individual so I won’t try to say whether he was a “philosopher,” “mystic,” “purveyor of crazy wisdom,” etc. Suffice it to observe that he was one of the most significant spiritual teachers of the 20th century. His teachings incorporated elements of Sufism, Buddhism, and Christianity while denying facile categorization into any one of these traditions, though Gurdjieff himself attested that the wellspring of his teachings was esoteric Christianity.

I will tell you the first commandment of God to man. This is not one of the commandments given to Moses, which were for a special people, but one of the universal commandments, which have always existed. There are many of them, perhaps twenty, but this is the first. ‘'Let one hand wash the other.’' It is very difficult for one hand to wash itself alone, but if one hand washes the other, both will be clean.

Gurdjieff’s teachings are often referred to as the “Fourth Way,” distinguishing them from the three traditional paths of spiritual development:

the way of the fakir,

the way of the monk,

and the way of the yogi.

The Fourth Way entails the transformation of everyday life into matter for spiritual work instead of retreating from the world before commencing. Gurdjieff emphasised the mechanical nature of ordinary consciousness: with the vast majority of our cognitive and emotional states we are succeeding only to “feed the moon” and in no way contributing to the development of ourselves or this cosmos. But, like Christ and like the Buddha, he did not end by diagnosing the problem with us, but also provided a solution. To this effect, he enjoined his students to engage in “self-observation” for the sake of becoming less meachnical in our lives.

Each time you feel the beginning of weakness, relax and then think seriously: “I wish the result of my weakness to become my own strength.” This will accumulate in you for your future work. Each man knows which weakness he has in him. Each time this weakness appears in you, stop yourself and do this exercise.

John G. Bennett, then head of the British Directorate of Military Intelligence in Constantinople, who would later become on of Gurdjieff’s most prolific students, describes his impression of Gurdjieff as follows:

It was there that I first met Gurdjieff in the autumn of 1920, and no surroundings could have been more appropriate. In Gurdjieff, East and West do not just meet. Their difference is annihilated in a world outlook which knows no distinctions of race or creed. This was my first, and has remained one of my strongest impressions. A Greek from the Caucasus, he spoke Turkish with an accent of unexpected purity, the accent that one associates with those born and bred in the narrow circle of the Imperial Court. His appearance was striking enough even in Turkey, where one saw many unusual types. His head was shaven, immense black moustache, eyes which at one moment seemed very pale and at another almost black. Below average height, he gave nevertheless an impression of great physical strength.

Gurdjieff’s other notable students include P.D. Ouspensky, Maurice Nicoll, and Jeanne de Salzmann.

From looking at your neighbor and realizing his true significance, and that he will die, pity and compassion (i.e. remorse of conscience) will arise in you for him and finally you will love him.

r Alfred Jules “Freddie” Ayer was born on this day, 1910.

A. J. Ayer, was an English philosopher known for his promotion of logical positivism, particularly in his books Language, Truth, and Logic (1936) and The Problem of Knowledge (1956).

In Language, Truth and Logic, Ayer presents the principle of verificationism as the only valid basis for philosophy. Unless logical or empirical verification is possible, statements like “God exists” or “charity is good” are not true or untrue but meaningless, and may thus be excluded or ignored. Religious language and moral statements, in particular, are unverifiable (according to his idiosyncratic definition of verification, which he shares with his fellow positivists and empiricists in history) and as such literally “nonsense.”

The presence of an ethical symbol in a proposition adds nothing to its factual content. Thus if I say to someone, "You acted wrongly in stealing that money," I am not stating anything more than if I had simply said, "You stole that money." In adding that this action is wrong I am not making any further statement about it. I am simply evincing my moral disapproval of it. It is as if I had said, "You stole that money," in a peculiar tone of horror, or written it with the addition of some special exclamation marks. … If now I generalise my previous statement and say, "Stealing money is wrong," I produce a sentence that has no factual meaning—that is, expresses no proposition that can be either true or false. … I am merely expressing certain moral sentiments.

—A.J. Ayer, Language Truth and Logic, Ch. VI. “Critique of Ethics and Theology”

In 1988, scarcely a year before his final departure from this world, Ayer wrote an article titled “What I saw when I was dead” that described a near-death experience. In his words, the NDE “slightly weakened my conviction that my genuine death ... will be the end of me, though I continue to hope that it will be.” But a few weeks later, he revised this, saying, “what I should have said is that my experiences have weakened, not my belief that there is no life after death, but my inflexible attitude towards that belief.”

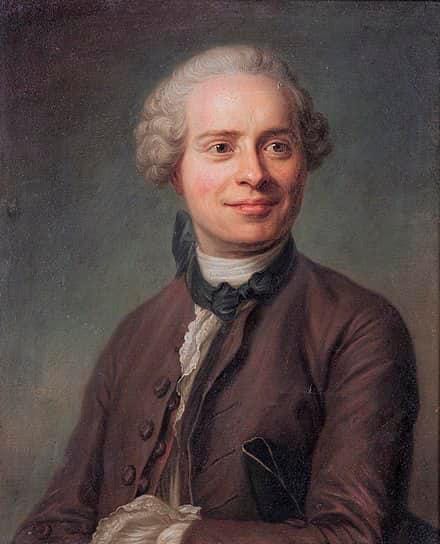

on this day, 1783 Jean-Baptiste le Rond d'Alembert completed his life

d'Alembert was a French mathematician, mechanician, physicist, philosopher, and music theorist. Together with Denis Diderot, d'Alembert served as co-editor of the famous Enlightement compilation, the Encyclopédie.

Encyclopédie was organised in the late 1740s, d'Alembert was engaged as co-editor (for mathematics and science) with Diderot, and served until a series of crises temporarily interrupted the publication in 1757. He authored over a thousand articles for it, including the famous Preliminary Discourse. D'Alembert "abandoned the foundation of Materialism" when he "doubted whether there exists outside us anything corresponding to what we suppose we see,” as Friedrich Albert Lange wrote of it in the 19th century. In this way, d'Alembert’s views resembled those of the absolute Idealist Berkeley and anticipated the transcendental idealism of Kant.

“D'Alembert's formula” for obtaining solutions to the wave equation is, as should be obvious, named after him.

The wave equation is sometimes referred to as “d'Alembert's equation,” and French speakers refer to the fundamental theorem of algebra by his name.

Ever erudite, Max! Thank you!